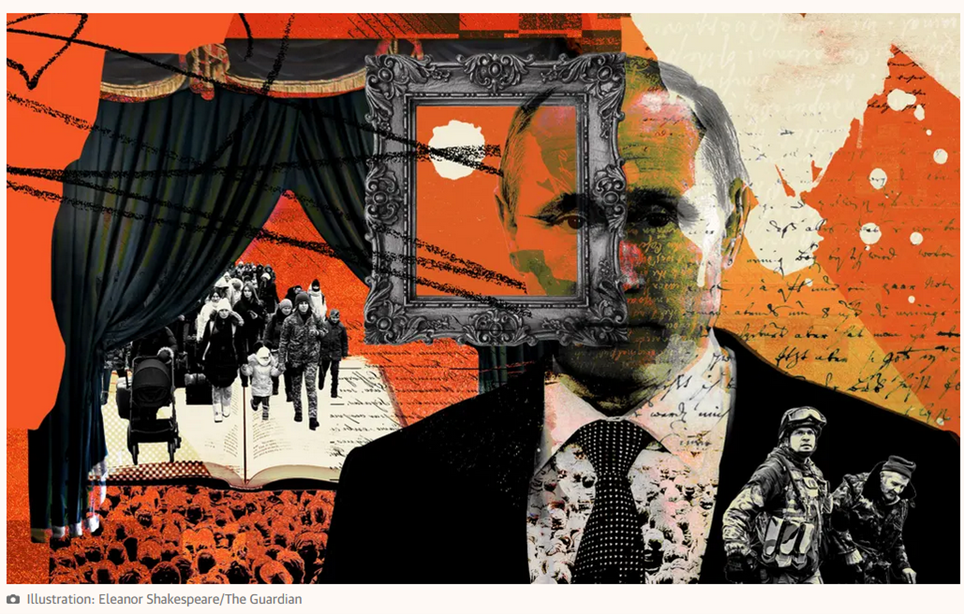

I faced Russia’s wrath for my TV series, Occupied. The Kremlin knows art can tell the truth about war – and it fears that

In 2015, the first season of Occupiedwas broadcast on Norwegian television. The series depicts a Russian occupation of Norway, something that is tacitly accepted by the EU and the United States as a way to restart oil production facilities that had been shut down by the green Norwegian government.

My aim for the show was to focus on the moral dilemmas faced by ordinary people in an extreme situation – to parallel what our parents and grandparents experienced during the German occupation of Norway between 1940 and 1945. The manoeuvring between a smaller country, a powerful neighbour and the rest of the world’s ruling nations, balancing political principles against economic considerations and their own security, was the backdrop.

I thought it would be obvious that the point of the fictional world in Occupied was not to say anything about Russia – just as Steven Spielberg’s aim in Jaws was not to say anything about great white sharks. However, the Russian authorities did not take it very well. Vyacheslav Pavlovsky, the ambassador to Norway, told the Russian news agency Tass that “it is certainly regrettable that in this year, when the 70th anniversary of the victory in the second world war is being celebrated, the authors have seemingly forgotten about the heroic contribution of the Soviet army in the liberation of northern Norway from the Nazi occupiers, and decided, in the worst cold war tradition, to frighten Norwegian viewers with a nonexistent threat from the east”.

It may be that the ambassador was a little touchy, because Russia had annexed Crimea the year before. But Occupiedhad been written and put into production long before that and it was a work of fiction in which, for once, the Russians weren’t depicted as a group of robotic, uniformly evil “bad guys”. So why the fury?

Perhaps the answer is that in an era in which the truth has been devalued by fake news, in which leaders are elected on a wave of emotion rather than their merits or political viewpoints, facts no longer carry the weight they once did. In writing about Russia’s latest war in Ukraine, a frequently used quotation comes from the US senator Hiram Johnson, who said in 1917 that “the first casualty, when war comes, is truth”. It is used, among other things, to remind journalists of just how vulnerable the truth is when two sides are fighting for the dominance of their own version of events.

In 1937, when the fascist General Franco bombed the town of Guernica, massacring the civilian population, many could testify to what happened. As soon as images of the destruction and the victims began to emerge, Franco and his generals realised the emotions they would stir both in Spain and abroad, and claimed that the Republican inhabitants had destroyed their own town. For a time, this version of events was believed – at least by those who wanted to believe it. But the Republicans had a better storyteller on their side. Pablo Picasso responded with one of his most famous paintings, Guernica, which depicted the inferno in the small Basque town. That work, painted by someone who lived in Paris and the product of an artist’s imagination and experience, opened Europe’s eyes.

If Guernicawas both propaganda and a masterpiece, the same can be said of Sergei Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin, commissioned by the Soviet authorities to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the 1905 revolution. Though both works purport to depict real events, they also make use of significant artistic licence – the famous massacre scene on the steps in Odesa never actually took place, for example.

But the narrator of fiction does not need to worry about such details; the aim is to say something true, not necessarily something factual. To move hearts and minds, not report on the who, what, where and when. This freedom is what gives fiction its power, particularly when we as an audience are unaware that we are being propagandised.

Tanner Mirrlees, author of Hearts and Mines: The US Empire’s Culture Industry, describes the way the US Office of War Information created a division to work with Hollywood during the second world war, the Bureau of Motion Pictures. Between 1942 and 1945, the Bureau reviewed 1,652 scripts, revising or removing anything that depicted the US in an unfavourable way, including material that made Americans seem “oblivious to the war or anti-war”.

Films were, and remain, the perfect vehicle for shaping popular opinion, Mirrlees said, because watching a film provides people with a galvanising, shared experience. Hollywood marketed American military ideals throughout the cold war, and it continues to do so even now.

Today, the entire world is essentially sitting in the same movie theatre, watching events unfold in Ukraine. But what we are seeing – figuratively speaking – are dubbed versions, featuring subtitles in our own languages. There is a battle under way between different versions of the story, and the best one will prove triumphant.

The question, therefore, is what measures we are prepared to take to win those hearts and minds, especially when Vladimir Putin is deploying the kind of censorship and propaganda we thought had been banished to the past. Is it desirable – or appropriate, even – to play by his rules? It seems contradictory that a democratic country would give up principles such as freedom of speech and transparency, even in an attempt to temporarily protect those freedoms.

We might hope that the truth – the imperfect, subjective truth of a journalist, an artist or some other storyteller who is trying to express something true – will win. There are examples of this, after all, such as a Soviet Union that collapsed from within or a Donald Trump who was thrown out of the White House. Faced with an exhausting tangle of different versions of reality, we do not have to give in and accept that every version is equally true. Some really are more true than others.

Putin’s narrative around why Russia has gone to war in Ukraine is gaining ground with a majority of Russians without access to social media or foreign reporting.

But the younger generation in Russia uses virtual private networks and other technological loopholes to access different views on what is happening. Their numbers are still small, but they are a resourceful group who will, themselves, eventually become journalists, writers and artists, using stories as weapons.

We follow the military developments, sanctions and diplomacy from day to day, but the war for the narrative is the long war. Ultimately, it is a war that Putin will lose.

Franco ruled Spain for almost 40 years. But in the end he was defeated in the history books. Guernicawas first shown in Spain in 1981, six years after Franco’s death. It was seen by more than one million people in the first 12 months alone, and is still one of the biggest draws at the Reina Sofia gallery in Madrid. Because the truest – if not the most factual – stories are the best.