Preserving Evidence Critical for War Crimes Prosecutions

Russian forces committed a litany of apparent war crimes during their occupation of Bucha, a town about 30 kilometers northwest of Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv, from March 4 to 31, 2022, Human Rights Watch said in a detailed report released today.

Human Rights Watch researchers who worked in Bucha from April 4 to 10, days after Russian forces withdrew from the area, found extensive evidence of summary executions, other unlawful killings, enforced disappearances, and torture, all of which would constitute war crimes and potential crimes against humanity.

“Nearly every corner in Bucha is now a crime scene, and it felt like death was everywhere,” said Richard Weir, crisis and conflict researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The evidence indicates that Russian forces occupying Bucha showed contempt and disregard for civilian life and the most fundamental principles of the laws of war.”

Human Rights Watch interviewed 32 Bucha residents in person and 5 others by phone, including victims and witnesses, emergency responders, morgue workers, doctors, a nurse, and local officials. Human Rights Watch also documented and analyzed physical evidence in the town, original photographs and videos provided by witnesses and victims, and satellite imagery.

The cases documented represent a fraction of Russian forces’ apparent war crimes in Bucha during their occupation of the town.

The chief regional prosecutor in Bucha, Ruslan Kravchenko, told Human Rights Watch on April 15 that 278 bodies had been found in the town since Russian forces withdrew, the vast majority of them civilians, and that the number was expected to rise as more bodies are discovered. Prior to the conflict, Bucha had a population of about 36,000.

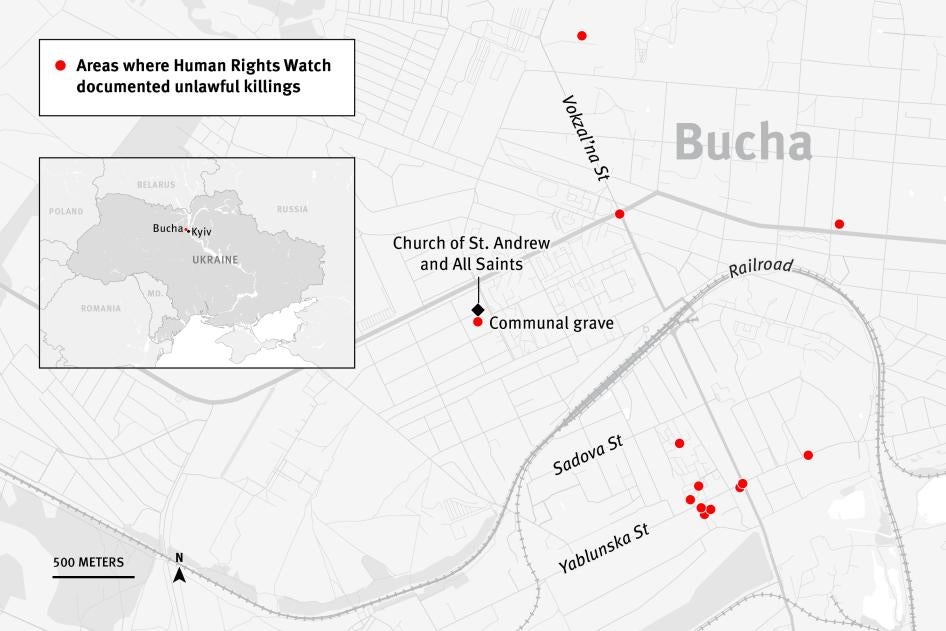

Serhii Kaplychnyi, head of the municipal funeral home in Bucha, said that, during the Russian occupation, his team placed dozens of bodies in communal graves outside the Church of St. Andrew and All Saints, after they ran out of space in the morgue. Only two of those buried were members of the Ukrainian military; the rest were civilians, he said. As of April 14, local authorities had exhumed more than 70 bodies from the church site.

Another funeral home worker, Serhii Matiuk, who helped collect bodies, said that he had personally collected about 200 bodies from the streets since the Russian invasion began on February 24. Most of the victims were men, he said, but some were women and children. Almost all of them had bullet wounds, he said, including around 50 whose hands were tied and whose bodies had signs of torture. Bodies found with hands tied strongly suggests that the victims had been detained and summarily executed.

Human Rights Watch documented the details of 16 apparently unlawful killings in Bucha, including nine summary executions and seven indiscriminate killings of civilians – 15 men and a woman. In two other documented cases, civilians were shot and wounded, including a man shot in the neck, as he was standing in his apartment on an enclosed balcony with his family, and a 9-year-old girl who was shot in the shoulder while trying to run away from Russian forces.

Human Rights Watch had previously documented a summary execution in Bucha that occurred on March 4, based on information from witnesses who had managed to flee Bucha. In that case, Russian forces rounded up five men and shot one of them in the back of the head, a witness said. In another case documented previously, on March 5, 48-year-old Viktor Koval died when Russian forces attacked the house where he and other civilians had been sheltering.

The Russian Defense Ministry denied allegations that its forces killed civilians in Bucha, stating in a Telegram post on April 3 that “not a single local resident has suffered from any violent action” while Bucha was “under the control of the Russian armed forces,” and claiming instead that the evidence of crimes was a “hoax, a staged production and provocation” by authorities in Kyiv.

Bucha residents said that Russian forces first entered Bucha on February 27, but were pushed out of the central part of the town during heavy fighting. On March 4, Russian forces returned, and largely took control of the town by March 5. Bucha then became a strategic base for the Russian forces’ efforts to advance toward Kyiv. Witnesses said that several Russian military units operated in Bucha during the occupation.

Soon after they occupied the city, Russian forces went door to door, searching residential buildings, claiming they were “hunting Nazis.” In multiple locations they looked for weapons, interrogated residents, and sometimes detained the men, allegedly for failure to comply with orders, or without providing a specific reason. Family members of those detained said they were not told where their male relatives were taken, and were unable to get information later about where they were being held. This amounts to an enforced disappearance, a crime under international law in all circumstances.

The bodies of some of those forcibly disappeared, including in two of the cases Human Rights Watch documented, were found on streets, in yards, or in basements after the Russian forces retreated – some with signs that they had been tortured. Ukrainian de-mining authorities said they found victim-activated booby traps placed on at least two dead bodies.

Russian forces occupied civilian homes and other buildings, including at least two schools, making these locations military targets. Two residents in one apartment building said that Russian forces ordered those remaining in the building to move into the basement, but to leave their apartment doors unlocked. Russian forces then moved in. When they found a locked door, they forced it open and wrecked the apartment, residents said.

Many residents said that Russian forces shot indiscriminately at civilians who had ventured outside. Vasyl Yushenko, 32, was shot in the neck as he went to smoke a cigarette in the enclosed balcony of his apartment. A nurse said she treated 10 people with serious injuries, including the girl who was shot while trying to run away from Russian forces. The man she was running with was killed and the girl’s arm had to be amputated.

Some people were injured or killed during explosions, funeral home workers said, most likely when the Russian forces were shelling the town at the start of their offensive or during artillery exchanges between Russian and Ukrainian forces.

Russian forces damaged the homes and apartments where they had stayed and also took private property, including, residents said, valuables such as television sets and jewelry. While occupying forces can requisition property for their use in exchange for compensation, looting – or pillaging as it is called under the laws of war – is strictly prohibited, in particular when property is taken for personal or private use.

Residents said they had limited access to water, food, electricity, heating, and mobile phone service during the occupation. One man said he buried his older neighbor, who had relied on an oxygen concentrator and died when the power went off and the machine failed.

Human Rights Watch has documented and received reports about other apparent war crimes in other towns occupied by Russian forces, such as Adriviika, Hostomel, and Motzyhn, and more evidence will likely emerge as access to other locations improves. A senior Ukrainian police official announced on April 15 that the authorities had identified 900 Ukrainian citizens across the Kyiv region who had been killed by Russian forces during their occupation but the circumstances of those deaths remains unclear.

Bucha’s chief regional prosecutor told Human Rights Watch on April 15 that over 600 bodies had been found across Bucha district, which is within the Kyiv region and has a population of about 362,000. Human Rights Watch has not verified these figures.

All parties to the armed conflict in Ukraine are obligated to abide by international humanitarian law, or the laws of war, including the Geneva Conventions of 1949, the First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions, and customary international law. Belligerent armed forces that have effective control of an area are subject to the international law of occupation. International human rights law, which is applicable at all times, also applies.

The laws of war prohibit willful and indiscriminate killing, torture, enforced disappearances, and inhumane treatment of captured combatants and civilians in custody. Pillage or looting is also prohibited. Anyone who orders or deliberately commits such acts, or aids and abets them, is responsible for war crimes. Commanders of forces who knew or had reason to know about such crimes but did not attempt to stop them or punish those responsible are criminally liable for war crimes as a matter of command responsibility.

Ukrainian authorities should prioritize efforts to preserve evidence that could be critical for future war crime prosecutions, including by cordoning off mass gravesites until professional exhumations are conducted, taking photos of bodies and the surrounding area before burial, recording causes of death when possible, recording names of victims and identifying witnesses, and looking for identifying material that Russian forces may have left behind.

Other governments, organizations, and institutions seeking to assist with war crimes investigations should work closely with Ukrainian authorities to ensure effective and efficient cooperation.

To support accountability efforts for serious international crimes, Ukraine should urgently ratify the International Criminal Court (ICC) treaty and formally become a member of the court, and authorities should work to align Ukraine’s national legislation with international law.

“The victims of apparent war crimes in Bucha deserve justice,” Weir said. “Ukrainian authorities, with international support, should prioritize preserving evidence, which is critical for ensuring that those responsible for these crimes will one day be held to account.”

Summary Executions

Human Rights Watch documented nine apparent summary executions in Bucha. Russian forces detained the men, in some cases forcibly disappeared and tortured them, and then executed them. Funeral home workers who buried the dead described seeing the bodies of dozens of other men who may have also been victims of summary executions. Many bodies were found on or around Yablunska Street, near the highway to Kyiv and just south of the train station.

Summary executions, irrespective of the victim’s status as a civilian, prisoner of war, or otherwise as a captured combatant, are strictly prohibited as a crime under international law and may be prosecuted as war crimes or crimes against humanity, depending on the context.

Execution on Yablunska Street

Iryna, 48, said that Russian soldiers shot at her two-story, multi-unit house on the corner of Yablunska and Vokzalna Streets at the start of their occupation on March 5. After an explosion and gunfire, the house caught fire. Iryna, who was at home with her husband, Oleh Abramova, and her father, Volodymyr, said that Oleh shouted that they were peaceful civilians and begged the Russian forces not to shoot. Four soldiers ordered them to come out of the house with their hands above their heads. The soldiers said they were there to free them from the “Nazis” and demanded to know where the Nazis were hiding.

“The soldiers accused us of killing people in Donbas,” Iryna said. “They accused us of killing the Berkut in Maidan as well [referring to the since-dissolved riot police unit that killed dozens of protesters during 014 Maidan protests in Kyiv]. They concluded that we were guilty and should be punished.” The soldiers ordered Oleh, 40, and Volodymyr, a pensioner, to extinguish the fire.

One soldier continued to question Iryna while three others took Oleh and Volodymyr to the northeast corner of the fenced-in yard. Volodymyr told Human Rights Watch that two soldiers then took Oleh out of the yard. Volodymyr said he pleaded for them to let Oleh come back to help put out the fire. One soldier went to look for Oleh outside the gate, but returned and said, “Oleh will not return.”

Within minutes, Volodymyr and Iryna said, they found Oleh’s body on the sidewalk outside the fence. “I saw that he was lying with his face down, and blood was pumping out of his left ear,” Iryna said. “The right side of his face was missing, and brain tissue and blood were coming out of his wound.” She said a group of soldiers was standing no more than five meters away, “watching the event as if they thought it was theater.”

Soldiers then told Iryna and Volodymyr to leave or they would be shot. Oleh’s body remained on the sidewalk until the Russian forces retreated on March 31 and the authorities removed it. On April 4 and 5, Human Rights Watch inspected the site and saw a large blood stain and what appeared to be human tissue on the pavement.

Enforced Disappearance, Apparent Torture, and Execution

In an apartment complex on Sadova Street, parallel to Yablunska, Russian forces detained Vasily Nedashkivskyi, 47, and his wife Tanya, 57, on or around March 17, after troops searched their home and found several weapons. Tanya said that Russian forces took them to the second floor of an adjacent apartment building, where they were held in separate bedrooms of a family’s apartment. Hours later, the Russian forces took Vasily out of the building and a soldier told Tanya that he would be taken to “headquarters” for questioning.

On April 6, Human Rights Watch visited the apartment and found traces of what appeared to be blood on the stairs leading to the apartment in which Vasily and Tanya were held, and evidence of the presence of Russian troops, including Russian military rations and camouflage clothing with patterns consistent with Russian uniforms.

Tanya said she was subsequently released, but the Russian soldiers did not give her any information about her husband’s whereabouts. Both Tanya and her neighbor, Oleksii Tarasevych, whom Human Rights Watch also interviewed, said that Russian forces generally prohibited residents in the neighborhood from leaving their buildings, except to get water, and even this was at times forbidden.

Vasily’s whereabouts remained unknown for nearly two weeks, Tanya said. His body was found in an outdoor basement stairwell in the building where they had been detained, along with the body of another man in civilian clothes, Igor Lytvynenko. Human Rights Watch reviewed photographs Tarasevych took on April 1. Human Rights Watch found two large dark red stains on the stairwell, apparently blood, that were consistent with the position of the bodies from the photographs.

In the photos, Vasily had severe lacerations on his hands, bruises on his lower abdomen, and what appeared to be blunt force trauma to his head. Tarasevych, who helped recover and bury Vasily’s body, said that they were not able to fully examine the body before burying him in a shallow grave behind the apartment building where Vasily and Tanya lived. Human Rights Watch visited the gravesite.

The fact that Vasily was last seen alive in the custody of Russian soldiers, and that his body had marks consistent with abuse, strongly suggest that after he was detained, he was tortured and summarily killed.

Execution in a Courtyard

On or around March 20, in the late morning, Russian forces occupying an apartment building on the corner of Poltavaska and Shevchenka Streets shot an unidentified man wearing a black track suit. A man and his 14-year-old son who lived in the building next door said they heard the shooting.

The father and son, interviewed together, said they were outside when Russian soldiers told them to go into their apartment and stay inside. Once in their apartment, both said, they heard a man quarreling with Russian troops in the rear courtyard of the adjacent building. Shortly afterward, the man yelled “Slava Ukraini!” [“Glory to Ukraine!” in Ukrainian]. Both the father and son then said they heard up to three shots. They looked out their apartment window and saw a man in a black track suit lying face down on the ground.

Because of the constant presence of Russian troops in the courtyard, where the soldiers often cooked food, it was two days before the father and two other men could bury the man’s body next to the apartment building in a shallow grave. Human Rights Watch separately interviewed one of those two men, a neighbor, who corroborated the father’s account of the burial but had not seen or heard the killing. Ukrainian authorities collected the man’s body on April 9; the father, son, and three other neighbors who had recently returned to the apartment building said they still did not know who he was.

Human Rights Watch visited the apartment building and saw the shallow grave and three apparent impacts from small caliber ammunition near where the father and neighbor said they had found the body.

Human Rights Watch reviewed two photos circulated on social media purporting to be of the body as it lay in the courtyard. In the photos, the man had duct tape wrapped around the upper portion of his head and around one of his wrists. From the photos, it appeared that his hands had been taped together but it is not clear if they were when he was killed.

Five Bodies in a Children’s Camp

On April 4, Human Rights Watch saw five bodies in the basement of a dormitory building in a children’s camp on Vokzalna St, 123, which some Russian forces in Bucha had used as their base. The bodies were of men wearing civilian clothes who appeared to have been killed by gunshot. There were three distinct bloodstains on the wall of the room. The hands of four of the men were zip-tied behind their backs. The fifth man appeared to have been shot twice in the chest – the stuffing of his thick jacket was protruding at two locations on his chest, which was covered in dried blood. One media report said that the authorities had identified the men as Serhiy Mateshko, Dmytro Shulmeister, Volodymyr Boychenko, Valery Prudko, and Viktor Prudko. The circumstances of their detention, including how they got to the basement, remains unclear.

There was extensive evidence that Russian forces had occupied the area, including two large “V”s – a symbol of support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – painted on the outside walls of the camp, discarded and consumed Russian rations, discarded uniforms of the pattern worn by Russian soldiers, and areas set up for making and eating food. Human Rights Watch observed evidence of tracked vehicle movement around the location and three positions for armored vehicles dug into the ground within 100 meters of the basement where the bodies were found. Human Rights Watch also saw three private vehicles in the children’s park, two with graffiti with the letter “V” alongside some numbers and the letters “RUS.”

Satellite imagery of the area on February 28 showed two large military vehicles at the camp entrance, next to a church. Satellite imagery from March 10 shows more vehicle tracks at the site. Satellite imagery from March 15 shows the three private vehicles at the site, two of them with the graffiti.

Bodies on the Northeast End of Yablunska Street

Human Rights Watch interviewed Denys Davydov, who recorded video footage as he walked along the northeast end of Yablunska street on April 1, just after the withdrawal of Russian troops. The video, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, shows seven bodies in civilian clothes, at least one of them with his hands tied behind his back.

The identities of the seven people and how they died remains unknown.

A video recorded from a moving car that was posted to Facebook on April 2 shows the same bodies in the same location. The video was recorded from a car as it drove in a convoy of at least three vehicles, one of which contains at least three uniformed Ukrainian soldiers, wearing blue armbands. Photographs taken on April 3 and published by Reuters show four of the bodies.

The man found with his hands tied behind his back was likely the victim of a summary execution.

Accounts from Funeral Home Workers

Serhii Kaplychnyi, the head of Bucha’s municipal funeral home, said he left the town on March 14 due to the deteriorating situation. When he returned on April 1, he said he found bodies at numerous locations with fatal wounds that indicate the people were likely to have been executed. “On Yablunska Street 144, I saw eight bodies of people who were shot, six of them with tied hands,” he said. “And the ninth body [at the same address] was a young man who we found inside on the stairs leading to the second floor. At first, I didn’t see any wounds. But when I was looking for documents and opened his coat, I saw a bullet wound in his heart.”

Further down Yablunska Street, Kaplychnyi said, funeral home workers collected about 20 other bodies, at least 10 of which had their hands tied. “In general, most bodies were shot from close range, mostly in the head, but not all of them,” he said.

Another funeral home worker, Serhii Matiuk, said he personally collected about 200 bodies from the streets of Bucha, starting in late February. “Almost all were killed with a bullet shot from a close distance, either in the head or in an eye,” he said. “Some lay on the sidewalk, some were in cars. Some of them were women.”

Matiuk said he encountered the first bodies with bound hands between March 4 and 6. “During the time of the occupation, I saw in total approximately 50 bodies with tied hands,” all of them men, he said. “The bodies had signs of torture. Their hands and legs were shot through. Some of their skulls were broken with blunt objects.”

Unlawful Killings of Civilians

Human Rights Watch documented seven cases of apparent indiscriminate killings of civilians by Russian forces in Bucha, as well as two cases of civilians wounded by Russian forces. Under the circumstances, Russian forces may have opened fire without knowing whether the person was a civilian. However, occupying forces are not permitted to presume that someone is a combatant, or poses a lethal threat, but must take steps to distinguish between civilians and military targets. Indiscriminate killings and indiscriminate use of force against civilians are prohibited under international law.

Killing on Yablunska Street

On March 5, on the northeast end of Yablunska Street, a man who wished to remain anonymous and his son-in-law, Roman, were hiding in their basement with their family due to the intense shelling and gunfire in the area. At about 4:30 p.m., the man said, when things were quieter, they opened their front gate to assess the damage. As Roman stepped out of the yard, his father-in-law heard a muffled sound and Roman fell to the ground. “I approached him and asked him if he was okay, and he just started moaning,” the man said. “I saw his coat from the left side was torn open.”

He and another family member immediately dragged Roman into the house. Roman’s sister-in-law, Tetiana, said they tried unsuccessfully to call a hospital and the Ukrainian territorial defense forces for help. Roman suffered all night and died the following morning at about 8 a.m. The family buried him in a shallow grave in their yard. Local authorities removed the body on April 6.

Shot and Injured While Smoking in His Apartment

A Bucha resident, Nikolaii, said that Russian forces fired at him and three members of his family at about 4 p.m. on March 7 when they were in the enclosed balcony area of their sixth floor apartment, where they had gone to smoke. Nikolaii and his sister, Iushenko Iryna, said that a single round pierced the glass in the exterior wall of the northeast-facing building and struck Iryna’s husband, Vasyl Yushenko, 32, just as he reached up to light his cigarette. The bullet tore through the front portion of his throat and hit the room beyond the enclosed balcony, where two children were sitting.

The family immediately took Vasyl out of sight of the glass enclosing the balcony, Nikolaii said. Minutes later, another shot hit the glass less than 10 centimeters from the first shot. The second bullet struck the wooden cabinet in the room beyond the window to the balcony area. A neighbor performed first aid and managed to save Vasyl’s life, Iryna said. The next day, Nikolaii, Iryna, and two neighbors took Vasyl two-and-a-half kilometers in a wheelbarrow to the hospital. He was later evacuated to Kyiv, where he was operated on twice and later discharged.

Human Rights Watch visited Nikolaii’s apartment on April 6 and observed the two impacts to the glass on the outside of the balcony area, blood spatters on the ground and against the window behind where Nikolaii said Vasyl was standing, what appeared to be remnants of human tissue, and two impacts of small caliber ammunition in the cabinets and wall behind the balcony. Based on the bullet impacts in the glass, cabinets, and wall, the shots were fired from somewhere northeast of the building. The fact that the two shots both hit nearly the same location indicates that these were not stray bullets and that Russian forces aimed at the figures they saw through the glass in the balcony area.

Shot and Killed While Getting Food

On March 20, Russian forces shot and killed Artem, 37, in his garage, where he had apparently gone to get jars of food after emerging from the basement of his apartment where he and his neighbors had been sheltering. Artem’s neighbor, Svitlana Nechypurenko, said that she saw two Russian soldiers near Artem’s garage, just south of Yablunska Street, from the window of her eighth-floor apartment. “I saw that they opened one of the garages, over there, with two ventilation pipes,” she said, pointing in the direction of the garage. “They opened the door, fired, and then they immediately shut the door and proceeded in the same direction. I heard two shots.” Residents speculated that Russian forces simply opened the garage door because they saw it was unlocked and then fired on whoever they saw inside.

Another neighbor, Andrii, said he went into the garage and found Artem’s body on March 20. He was lying on his back with a broken glass jar of Adjika, a spicy dipping sauce, at his feet, with the sauce covering his legs. Andrii later buried Artem’s body behind the garage.

Before the Russian invasion, Artem had worked on a military base painting vehicles for the Ukrainian military, but he had spent the prior 15 days sheltering in the basement, Andrii said. Nechypurenko, who was sheltering with Artem, said that Artem had routinely provided food from his supplies to others in the shelter during the occupation.

Killing Near Yablunska Street

On the evening of March 12, Russian soldiers shot and killed Ilia Navalnyi, 61, near an apartment complex on Yablunska Street as he left the home of his friend, Alexii, 71. Alexii did not witness the killing, but he and another building resident said that, just before the killing, they saw a Russian soldier outside the building, firing his weapon across the yard. In the morning, another neighbor found Ilia’s body, Alexii said. When Alexii got to the location, about 15 meters from the entrance to his building, he found the pages of Ilia’s national ID torn out and scattered across the ground around the body.

Older Man Killed

Two Bucha residents, Mykola and Serhii B., interviewed separately, both said that on or around March 8 they saw the body of an older man slumped over on his side next to his walker near a memorial to Soviet soldiers at the corner of Nove Highway and Vokzalna Streets. The two men said he appeared to have been shot. Human Rights Watch inspected the location and found extensive damage to the surrounding buildings, damaged vehicles, and vehicle tracks around the memorial, indicating that this was likely an area where Russian forces had operated. Who the man was and how he died remain unclear.

Man Killed and Young Girl Injured on Yablunska Street

Around March 5, Russian forces shot and killed Volodymyr Rubailo, and seriously injured a 9-year-old girl who was with him in the arm, as they were running from Russian forces on Yablunska Street. Rubailo apparently died in front of an apartment building.

Two witnesses, interviewed separately, said that neighbors took the girl into the basement of a nearby building, where they attempted to treat her wounds. Victoria, an emergency nurse who lives in a house next to that building, went to help two days later, when the girl’s condition deteriorated. Victoria said that the tissue of the girl’s shoulder had already begun to die and that the girl’s arm was later amputated at the hospital. Human Rights Watch was not able to identify the girl or verify this claim.

Human Rights Watch, with another neighbor, Oleksii, 71, visited the site on April 5 where Rubailo and the girl were shot and observed large blood stains on the ground approximately 5 meters apart from one another.

Missing Man Later Found Dead

A resident of Bucha, Oleh, 33, had been missing since March 19, said Luda, a neighbor. Twelve days later after the Russian forces had retreated, residents found his body under a pile of metal sheeting, meters from his apartment building, she said.

Human Rights Watch visited the site where his body was allegedly found and saw a large blood stain. It was about 10 meters from the house where the commander of one of the Russian military units was reportedly staying, local residents said. Human Rights Watch visited that building and found Russian camouflage uniforms and ration packages. Satellite imagery collected on March 11 shows a military vehicle parked at the site where Oleh’s body was found.

Human Rights Watch could not establish how long Oleh’s body had been where it was found, but the large amount of blood at the site suggests that he was either killed there or was placed there while severely injured. The continuous presence of Russian forces in that area means that they most likely would have known about the killing. It is unclear whether Russian forces made any attempt to locate Oleh’s family, but one resident interviewed said that Oleh’s wife learned of his death only after Russian troops had left and residents found the body.

Russian Armored Vehicles Fire at a Woman with Bicycle, Killing Her

Iryna, the wife of Oleh Abramov, who was killed on March 5, said that she saw the body of a woman lying next to a bicycle a few meters from their gate, just after Russian forces shot and killed her husband and then ordered her to walk southeast down Yablunska Street.

The woman near the bicycle is most likely the same person whose death was captured on aerial footage that was posted to Telegram on April 5. The video, analyzed by the New York Times, shows a cyclist dismount from their bicycle as she turns down Yablunska Street before being fired upon by two Russian armored vehicles. At least 19 military vehicles line Yablunska Street and the parallel streets.

Satellite imagery analysis indicates that the aerial footage was recorded sometime between February 28 and March 9. Satellite imagery from February 28 shows the same destroyed armored vehicles that are visible in the footage, while imagery from March 9 shows destroyed houses that are still intact in the video.

Victim-Activated Antipersonnel Mines and Booby Traps

Human Rights Watch spoke with the head of the Ukrainian government’s de-mining unit for Bucha region, Lt. Col. Roman Shutylo, as well as the commander of an anti-tank brigade assisting with demining in Bucha, Ihor Ostrovsky. Both reported that victim-activated booby traps had been used in the town. Shutylo said that on April 8 the deminers had found two dead bodies that had victim-activated booby traps placed on them. In total, they found 20 victim-activated booby traps and anti-personnel mines, including those constructed with the F-1 and RGD-5 fragmentation hand grenades, as well as MON-50, MON-100, and OZM-72 mines.

Ostrovsky shared video of an ordnance item attached to wire, which he said was found in a yard in Bucha, that had been configured to detonate when enough tension is exerted on the wire. The de-mining team said they found at least one other similar device in a building that Russian troops had occupied. A third de-miner in Bucha showed Human Rights Watch a photograph on his phone that he took of one of the two victim-activated improvised explosive devices his team uncovered in Bucha.

The 1997 International Mine Ban Treaty comprehensively bans the use, production, stockpiling, and transfer of antipersonnel mines and other devices such as victim-activated booby traps. While Ukraine signed the international mine ban treaty in 1999 and became a state party in 2006, Russia is not among the 164 countries that have joined the treaty.

Looting by Russian Soldiers

Human Rights Watch found evidence in multiple locations across Bucha that Russian soldiers used and damaged homes, some of which they occupied, and also took provisions, household goods, and other personal belongings including valuables such as appliances, television sets, and jewelry. One man said that Russian soldiers broke in and looted his and his neighbor’s home after they had fled Bucha. In the homes, Human Rights Watch saw Russian equipment and bloodied bandages, as well as damage to the two properties.

Denys said that he saw household items piled onto military vehicles as Russian forces left his neighborhood on March 31. “I was looking out of my house to see if I could see any of my personal belongings or my neighbors’ as they drove away,” he said. He added that the Russian forces who had entered his home used a grinder to open his personal safe where he kept important documents, and they also damaged numerous other items in his home.

Tarasevych, who lived in another neighborhood, took a photograph on March 21 that Human Rights Watch reviewed of a Russian vehicle loaded with items on the roof, which included personal belongings of residents as the soldiers left the apartment complex that they had occupied. Tarasevych said that when another group of Russian soldiers left the same apartment complex on March 31 at about 5 a.m., they also carried away personal items from the apartments that they had occupied. “I saw trucks packed with big civilian bags, and it was obvious that it wasn’t military equipment,” he said. Human Rights Watch is aware of alleged intercepts and reports of Russian soldiers discussing luxury goods they have stolen to bring home, but has not been able to verify these reports.

Russian Forces Endangering Civilians in Bucha

Based on interviews with residents, satellite imagery analysis, and site inspections, Human Rights Watch was able to trace the position of Russian forces at various stages during the time they occupied Bucha. Human Rights Watch heard that Russian soldiers ordered Ukrainian civilians to stay in residential buildings, but then positioned their personnel and equipment near those buildings during their occupation, thereby failing to take all feasible precautions to minimize harm to civilians and damage to civilian objects.

Satellite imagery collected on March 19 shows at least two military vehicles parked on the adjacent streets of an apartment complex 350 meters north of Yablunska Street. Satellite imagery collected on March 31 shows vehicle track marks on the pavement all around, indicating the regular passage of Russian military vehicles in that area. This is consistent with the videos and photos that Tarasevych shared. He took photos and videos of Russian personnel, military vehicles, and equipment during multiple days of the occupation. Russian forces also maintained an 82-millimeter mortar position about 20 meters from where civilians were living along Sadova Street.

Human Rights Watch also found that Russian forces occupied the grounds of two schools in Bucha. At one location Human Rights Watch found extensive evidence that Russian forces had used it as a firing position for artillery.

The Safe Schools Declaration, endorsed by Ukraine and 113 other countries but not Russia, says that countries should not use educational facilities for military purposes and should take other steps to protect education from attack.

Evidence Preservation

From April 4 to 10, Human Rights Watch had access to sites where evidence of apparent war crimes remained after the Russian forces retreated, and was intermittently present during the handling of war crimes evidence in Bucha, including the exhumation of human bodies from a communal grave located next to the Church of St. Andrew and All Saints.

On April 4, authorities removed the bodies of five men who appear to have been executed by Russian forces from the basement of one of the dormitories at a children’s camp on Vokzalna Street 123. Human Rights Watch, along with dozens of media personnel, were allowed to access the site prior to removal of the bodies but is not aware what steps were taken to log and preserve physical evidence at the site prior to being granted access. When the authorities removed the bodies, they placed them in the courtyard in open body bags. Officials then cut the zip ties off the wrists of four men in front of the media, discarding the zip ties on the ground. They were subsequently removed.

For at least a week after the Russian forces retreated, bodies were strewn along the streets and in various other locations, with others hastily buried in shallow graves. Physical evidence, such as bloodied clothing and personal effects, were still at the sites where bodies were recovered. Other possible evidence, such as bullet casings, littered the streets of Bucha. Human Rights Watch is not aware of the steps taken by authorities to secure this evidence.

On April 8, authorities began exhuming bodies from the communal grave located next to the Church of St. Andrew and All Saints. Human Rights Watch observed the exhumations on April 8 and 10 and saw that authorities were wearing protective clothing and engaged in photo and video documentation of the bodies throughout the process, recording information about each of the bodies before removing them from the site.

Physical evidence will be most valuable for future war crimes prosecutions if it is well-documented and preserved as soon as possible following the commission of the alleged crimes, limiting opportunities for evidence to be damaged or destroyed. In addition to prioritizing efforts to document and preserve physical evidence in Bucha and other areas, Ukrainian authorities and their international partners should work to develop robust systems for storing and organizing evidence. Efforts should also be made to enhance coordination among the various actors supporting national, regional, and international investigations.

Bolstering Accountability Efforts

Various national and international jurisdictions have opened investigations into apparent war crimes and other serious crimes committed in Ukraine, including Ukrainian authorities, the ICC, and third countries, such as Germany, using the principle of universal jurisdiction. The United Nations Human Rights Council also established a Commission of Inquiry into serious human rights and international humanitarian law violations in Ukraine, and its work could provide important assistance to the ICC and other judicial authorities.

To support these and other accountability efforts, Ukraine should urgently ratify the ICC treaty and formally become a member of the court. National and international civil society have for years been pressing the authorities to join the court. Ukraine is not a member of the ICC, but it accepted the court’s jurisdiction over alleged crimes committed on its territory since November 2013. On March 2, 2022, a group of ICC member countries referred the situation in Ukraine to the court’s prosecutor, Karim Khan, for investigation. After receipt of the referral, Khan announced that his office would immediately proceed with an inquiry and has since traveled to Ukraine.

A domestic law aligning Ukraine’s national legislation with international law is also needed to bolster national authorities’ ability to build the legal framework necessary to support the effective domestic investigation and prosecution of international crimes. The absence of domestic legislation has been one of the key barriers in domestic accountability efforts. A bill adopted by Ukraine’s parliament on May 20, 2021 could help authorities prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity domestically. However, it has not been signed into law by Ukraine’s president and there is no update on its status.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch first traveled to Bucha on April 4 with an organized media tour that was mandated by the Ukrainian government for access to the area due to security. During that trip, the group was taken to see a children’s camp where five dead bodies lay in the basement of a building that was guarded by police. Human Rights Watch was able to visit multiple sites around Yabalunska Street without supervision.

From April 5-10, Human Rights Watch worked alone and unhindered in Bucha, visiting sites and interviewing witnesses, victims, and local officials. During this time and thereafter, Human Rights Watch also analyzed satellite imagery and photos and videos provided directly by witnesses and victims, as well as those posted online.

Interviews were conducted in Ukrainian with the assistance of an interpreter. Many of the people interviewed requested anonymity or use of only their first name due to security concerns. No benefits or compensation were offered or provided to people interviewed.

Human Rights Watch previously started researching incidents in Bucha and environs from around March 7, while Russian forces still occupied the area, through telephone interviews and in-person interviews with people who had managed to flee the area.