ZYUM, Ukraine — About 10 days before Ukrainian forces retook the city of Izyum last weekend, Russian troops stationed here were so demoralized that they drafted letters begging their superiors to dismiss them from their roles.

The 10 handwritten letters, dated Aug. 30, were left behind in a two-story residential house where Russians were squatting. Ukrainian soldiers later found the letters and provided them to The Washington Post for review. They paint a portrait of dejected troops desperate for rest and concerned about their health and morale after months of fighting.

“I refuse to complete my duty in the special operation on the territory of Ukraine due to lack of vacation days and moral exhaustion,” wrote a man who identified himself as the commander of an antiaircraft missile platoon from the Moscow region.

Another soldier asked to be released, citing “the worsening of my health and not receiving the necessary medical aid.” Still another said he was experiencing “physical and moral exhaustion.”

Others wrote complaining that they were denied vacation time for family obligations, including to get married and to witness the birth of a child.

The similar style in which the 10 letters were written suggests the troops, weary and disheartened, banded together to draft them. The letters caught the attention of Ukrainian soldiers when they first arrived in Izyum, which the Russians abandoned hastily in retreat, and some were shared on social media.

The authenticity of the letters has not been confirmed by independent forensic experts, but the original documents provided to The Post for review were among the heaps of belongings — from boots and uniforms to colorful letters of support from Russian schoolchildren — that were abandoned as the Russians fled from a remarkably rapid Ukrainian advance that put nearly all of the Kharkiv region back under Ukrainian control in a matter of days.

An Aug. 23 report addressed to the commander of Russia’s 2nd Motorized Rifle Division labeled “TOP SECRET” and “extremely urgent” was also left in the same house, describing how four Russian troops were killed and one was wounded by Ukrainian artillery fire in the village of Kamyanka, about 75 miles north of Izyum near the Russian border.

Altogether, the contents of the house help to reconstruct the remarkable turn of events that led to the swift Russian withdrawal from Kharkiv region, where in many cases troops fled after barely putting up a fight.

Here’s what Russian soldiers left behind when they withdrew from Izyum

Once the Ukrainians began their push toward Izyum, the Russians who had been based here for months had just enough warning time to destroy what they could on their way out.

They set fire to the city council building where they had installed a puppet government, ignited explosives on some of the military hardware they planned to abandon and blew up a strategic bridge. In the process, civilians said, they left some of their own forces stranded on the other side with no choice but to walk or run across the damaged bridge to leave.

Shortly before the Ukrainians reclaimed the city, residents said, the Russian troops imposed a 24-hour curfew, then entered civilian homes and raided closets for mismatched clothing to avoid being seen in their uniforms. Some then fled on foot or by bike, the residents recounted.

Before stealing locals’ clothes, “they didn’t even pay attention to who was living there or if it was someone their age, they just opened their closets,” said Tanya Lukianinka, 32, who crossed the broken bridge and walked downtown with her daughter and friends on Wednesday carrying Ukrainian flags in an act of celebration.

Lukianinka’s daughter, Henrietta, 14, said she learned about the curfew on Russian radio stations — but by tuning to Ukrainian channels began to understand why Russian forces were suddenly so worried.

“We heard that somewhere on the outskirts of Izyum they’d raised a Ukrainian flag,” she said. “We were very happy.”

Vasil Tuskaniuk, 23, who joined the group on the walk downtown, said it was his first time visiting the area since before the Russians took control of the city. Born in western Ukraine, he feared he would be detained and deemed a threat to Russian forces if they searched his documents. To avoid interacting with Russians, he did not leave his property for the entirety of the invasion.

“It’s possible I wouldn’t have returned home,” Tuskaniuk said.

Ukrainian offensive thwarted Russia’s annexation plans in Kharkiv

Over the months of occupation, Henrietta said she heard stories of people being killed or detained in Russian basements and subjected to electrical shocks. Russian newspapers advertised camps for children in Russia, she said. One of her friend’s sisters, who was around 15 years old, left for such a camp and still has not returned, she said.

The Russians intended to open schools in Izyum just before the Ukrainian advance thwarted their plans. “We didn’t put our kids on the enrollment list,” Lukianinka said. “They were just trying to spread propaganda.”

Russian propaganda was omnipresent, Lukianinka said, but it did not change hearts or mind. Rather, she said, the messaging appealed mainly to the people who were already Russian sympathizers. Some of those people remain in the city, she said, adding that she hoped they would change their views now that Ukraine has retaken control.

The letters describing the soldiers’ lack of will to fight stand in stark contrast to the pile of schoolchildren’s letters from a city near Moscow encouraging the troops — a clear example of how the Kremlin’s narrative over the war is being portrayed in Russian schools. Still, even children in Russia seemed aware that soldiers fighting in Ukraine were facing difficult circumstances.

“Hello, I don’t know who will receive this letter but I know you’re having a really hard time right now,” a girl named Nastya wrote. “That’s why I want to support you. It’s possible you’re hungry, you’re cold, you want to go to home to your family or maybe you want to go back to your friends from your childhood.”

A boy named Leonid wrote: “You’re protecting peaceful civilians, you’re fulfilling the main duty of every man. I think that war is something very bad and scary. There is death of innocent people, destruction, when you can’t live a normal life, when you’re left without a home, without work, and you lose your close ones. I hope you hang in there and manage to achieve complete victory! Good luck! I believe in you!”

“I very much appreciate the hardship you’re going through,” a boy, Pasha, wrote, noting he is in the fourth grade in the city of Mytishchi just north of the Russian capital in the Moscow region. “I’m grateful to you that we live under a bright and clear sky.”

Another boy, Geydar, wrote: “I see how you are battling in Ukraine. I wish for your family to be very proud of you. I hope you’ll end up winning and if you have kids you’ll be a hero in their eyes.” The child added, “I see everything that is happening there. Russian people are dying. Win the war, see you.” Beneath the words, he drew stick figures facing each other holding Russian and Ukrainian flags.

At the entrance to the recently liberated city on Wednesday, under the sign for Izyum, a dirty Russian flag lay crumpled on the soggy ground.

One elderly woman walking near the broken bridge on Wednesday said her husband died in a rocket attack on June 9. She declined to elaborate on her experience, saying she had suffered too much already.

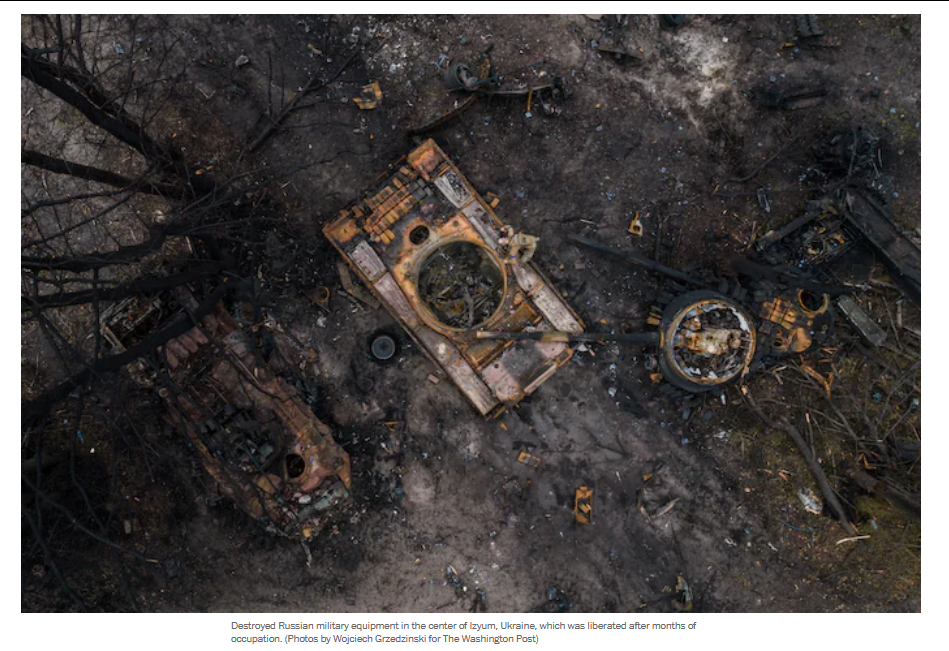

The area around the city’s main square now looks apocalyptic.

Nearly every building is damaged if not destroyed. Shops are completely looted. One shop owner painted “No beer or vodka” on the outside of his store. Someone else painted a “Z” on top of the message. Ukrainian troops were positioned throughout the city, some directing traffic away from roads blocked by abandoned equipment and others helping move traffic across a pontoon bridge hastily set up to allow traffic to move between two sides of town.

On a surprise visit to Izyum on Wednesday, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky declared that Ukraine’s blue-and-yellow flag would fly “in every Ukrainian city and village.”

Hours after his visit, a woman in a red coat walking downtown appeared apprehensive about the jubilance over Ukraine’s rapid success. “Are you sure the Russians aren’t coming back?” she asked.

The area around the city remains treacherous as Ukrainian forces work to clear the roads of mines and of the many damaged tanks and other equipment abandoned on the outskirts.

Post reporters were turned away on one road leading into Izyum, where soldiers warned the roads were still heavily mined. An unexploded antitank mine could be seen on the side of that road, a field of yellow sunflowers growing just behind it.

As civilians emerged cautiously from their basements and homes, there were some small moments of joy that had been denied to them over so many months of occupation.

Neighbors greeted each other across their fences. Some rode their bicycles through the city’s central square. Lukianinka’s group gathered around an “I LOVE IZYUM” sign downtown, beaming as they held up their flags.

A driver for The Post, who is from Izyum and had not seen his parents since before the invasion, knocked on their gate on Wednesday afternoon. Their house was damaged by shelling, and Russian troops had even tried to sleep there, until his mother told them off.

When his 60-year-old father pulled the door open, the son scooped him up in a hug — his father beaming over his shoulder. Then his mother came running outside, weeping with joy as she threw herself into his arms.