Ukrainian officials this week staged an exercise in case of possible nuclear disaster

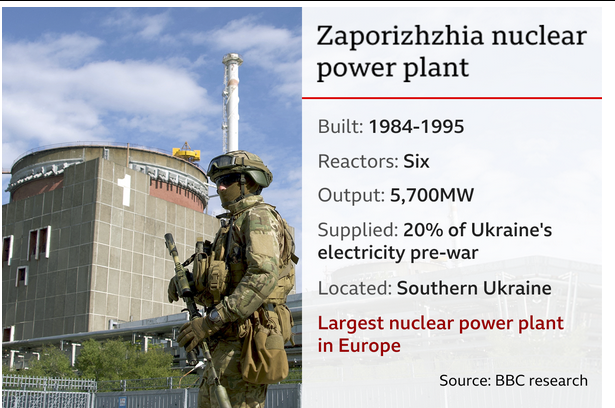

The rhetoric surrounding Europe’s biggest nuclear power plant – close to the front line in Ukraine – is becoming increasingly alarming, with international figures warning of the risk of a major accident.

UN Secretary General António Guterres believes potential damage to the Zaporizhzhia plant could be “suicide” and Turkey’s president has said no-one wants another Chernobyl – the world’s worst nuclear accident, when Ukraine was under Soviet rule.

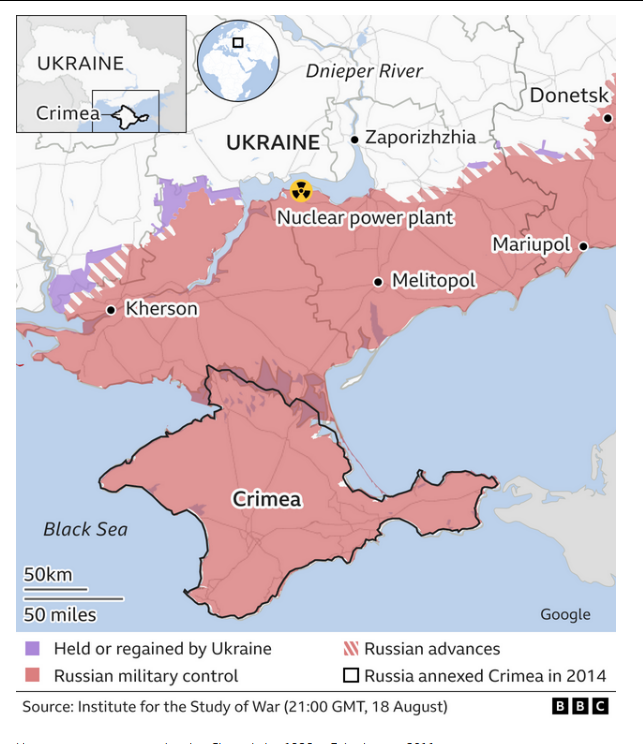

Russia seized the site on the left bank of the River Dnieper at the start of its war, Ukraine says a Russian film crew has already staged an attack to blame on Kyiv.

Russian defence officials have produced a map showing how a radioactive cloud might spread from the plant from Ukraine to neighbouring countries, including Hungary, Poland and Slovakia.

A potentially more serious hazard could come if the power supply to the nuclear reactors and back-up generators was lost and led to a loss of coolant. With no electricity to power the pumps around the hot reactor core, the fuel would start to melt.

The UN’s atomic energy authority, the IAEA, warns of a “very real risk of nuclear disaster” and has asked to be allowed access to the site as soon as possible. The UN secretary general has called on Russia to pull its troops out and demilitarise the area with a “safe perimeter”. Russia has refused, arguing that would make the plant more vulnerable.

Map showing the location of key components of Ukraine’s largest nuclear power plant

Ukraine’s nuclear agency says three of the four power transmission lines linking the plant to Ukraine have already been damaged by rocket fire. If the last source of power is also broken, the agency believes nuclear fuel will begin melting “resulting in a release of radioactive substances to the environment”, and diesel generators will not provide a long-term solution.

Another major safety fear could come from the spent fuel at Zaporizhzhia. Once the fuel is finished the waste is cooled in spent fuel pools and then moved to dry cask storage.

At the heart of this crisis are the plant’s original staff, working under Russian occupation and quite probably under a great deal of stress. They have complained of the plant coming under continuous attack but warn the real threat of disaster would emerge if Russia shut the whole plant down, so it could disconnect the supply from Ukraine and reconnect it instead to Russian-occupied Crimea.

Dr Wenman believes it is the human factor that represents the biggest risk of a nuclear accident, whether because of chronic fatigue or stress: “And that violates all the safety principles.”

If something were to go wrong, they would need to be on top form, and one can imagine they are not, says Claire Corkhill.

The head of the IAEA, Rafael Grossi, appealed for the staff to be left to carry out their duties “without threats or pressure”.

A letter signed by dozens of employees at the plant on Thursday called on the international community to stop and think: “We can professionally control nuclear fission,” it said, “but we are helpless in the face of people’s irresponsibility and madness.”