The reopening of Notre-Dame de Paris after a devastating fire and extensive restoration was not only a cultural milestone but also a global political event. It emerged as a symbol of commitment to preserving shared heritage and the triumph of culture over tragedy.

The deep roots of Western civilization in the world’s cultural legacy enable the wielding of “soft power” – a force that strengthens diplomatic ties, promotes cultural diplomacy, and shapes the influence on modern geopolitics and international cooperation. This time, the “soft power” embodied in the cathedral’s stunning architecture became a magnet, drawing global political figures to this event.

World leaders attend the grand opening ceremony of the cathedral following its restoration. December 7, 2024

Victor Hugo once wrote about the creation of the cathedral: “There exists in this era, for thoughts written in stone, a privilege comparable to our current freedom of the press. It is the freedom of architecture.” Inspired by this embodiment of freedom rendered in stone, Western political leaders paused their affairs to pay homage — not merely to the building of the cathedral, but to a symbol of freedom that urges collective action in its defense.

France played a particularly significant role — not only in fostering the unity of Western societies and collaborative efforts to preserve cultural heritage. The event, among other things, became an occasion to strengthen the dialogue on a just end to Russian aggression against Ukraine and an end to the war. A standing ovation greeted Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky upon his arrival at the cathedral. Moreover, the negotiations held during the visits of world leaders to Notre-Dame bolstered Ukraine’s international standing and reinforced its pursuit of a just peace.

Volodymyr Zelensky, Emmanuel Macron, and Donald Trump during a meeting in Paris

Thus, the revival of the majestic cathedral can be seen as a metaphor for the revival of Europe’s leadership and its ability to jointly overcome challenges and tragedies. The gravest among these is Russia’s full-scale aggression against Ukraine and the outbreak of war on the continent. This war risks spreading to other countries, given the irresponsible political statements from the Russian Federation, Belarus, and Iran, as well as rhetoric from certain American speakers within the framework of realpolitik, suggesting that EU countries should take on a greater role in providing effective support to Ukraine to achieve a just peace.

During a meeting with Nela Riehl, Chair of the European Parliament’s Committee on Education and Culture

The reopening of Notre-Dame after the tragic events could serve as a symbol that Europeans will remember who they are and the place they occupy in the history of the world. It is a reminder of how the European family developed and grew after the First and Second World Wars, when geopolitical processes and militarism divided the continent’s cultural space, leaving people and the meanings they created on opposite sides of the Berlin Wall and the “Iron Curtain” of the Warsaw Pact.

In particular, Czech author Milan Kundera addressed this division in his renowned essay “The Tragedy of Central Europe” (1983). In 2023, the global cultural and literary community marked the 40th anniversary of this work with extensive discussions. The essay became a manifesto for the cultural identity of Central Europe, a region that, due to geopolitical processes, was “Western culturally, but Eastern politically,” “kidnapped” by the Soviet Union, and forced to exist under the suppression of its cultural and political essence.

The global significance of the reconstruction of Notre-Dame de Paris after the tragedy, coupled with the ongoing discussion of the “kidnapping of Europe” since the onset of Russian aggression against Ukraine in 2014, heightens the expectation that Europe will finally “wake up” and confront the existential threats posed by the criminal actions and genocidal rhetoric of Russia’s political leadership.

Kundera’s “Tragedy of Central Europe” underscores that the calls to “wake up,” directed at European political leadership over the years, have been dictated by the imperial threats posed first by the Soviet Union and later by the Russian Federation.

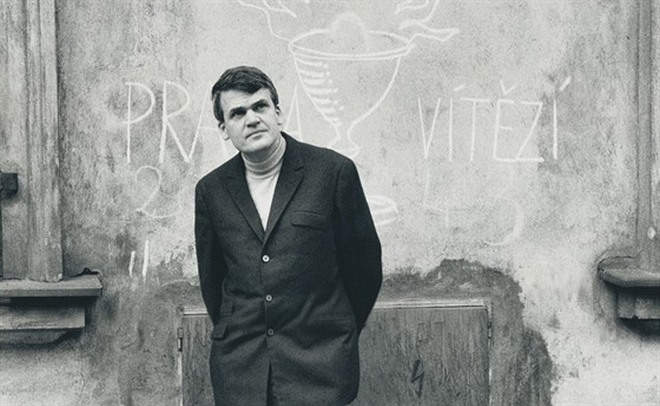

Milan Kundera

Kundera wrote: “In November 1956, the director of the Hungarian News Agency, shortly before his office was flattened by artillery fire, sent a telex to the entire world with a desperate message announcing that the Russian attack against Budapest had begun. The dispatch ended with these words: ‘We are going to die for Hungary and for Europe.'”

Kundera’s words posed a profound question: were all European capitals prepared to “die for Europe”? The ongoing war in Ukraine, which has already claimed tens of thousands of lives in defense of a civilizational choice, reveals that this question remains unanswered.

Russian aggression in Ukraine represents a continuation of the same imperial policy that once sought to assimilate Central Europe.

During a meeting with the Secretary General of the Council of Europe, Alain Berset (right), and Eric Thill, the Minister of Culture of Luxembourg

The concept of Central Europe, along with the role of Russian tanks in suppressing its identity, was a central topic of discussion at the 1988 Lisbon Conference on Literature. Russian writers were also invited to this gathering, but they came as representatives of the Soviet Union — a state that formally united various republics and ethnicities. Yet, the participants from the Soviet Union identified themselves as representatives of Russian writing and Russian literature.

In response to a question from Hungarian writer Gyorgy Konrad about the attitude of Russian writers toward the concept of Central Europe, as described by Milan Kundera in his essay, the Russian writers stated that they did not recognize Central Europe as a distinct entity.

Joseph Brodsky, in particular, remarked that “the problems of Eastern Europe will be solved as soon as Russia’s internal problems are solved.” By this, he implied that the efforts of Russian intellectuals were directed exclusively toward Russian issues, and they deemed it unproductive to concern themselves with the affairs of others.

American writer and literary critic Susan Sontag emphasized that the refusal to accept the concept of Central Europe and its subjectivity revealed the imperialist stance of the Russian participants, a position they certainly did not acknowledge.

Russia’s war against Ukraine, beginning in February 2014, bears the character of punishment from the empire for the Ukrainian people’s choice of freedom and their own subjectivity. However, a decade ago, not everyone in Europe saw it that way. And not all in the long-suffering Central Europe perceive Russian aggression as yet another attempt to destroy the cultural identity of the former colony.

Evidently, the imprint of Russian tanks remained so deeply ingrained in the Hungarian consciousness that, even after they left Hungarian territory, some politicians today promise to do everything possible to prevent Ukraine from joining NATO or the EU.

The rejection of another identity and subjectivity is a hallmark of traditional Russian imperial policy. An example of this can be found in the article “On National Identity and Political Choice: The Experience of Russia and China” by Dmitry Medvedev, Deputy Secretary of the National Security Council of the Russian Federation. The article was published following his visit to Chinese leader Xi Jinping, likely with the intention of publicly consolidating the messages he had conveyed to Chinese interlocutors during their negotiations.

Medvedev’s goal is to strengthen the central Kremlin imperial narrative by crafting a clear and transparent message for the Chinese elites that denies the existence of Ukraine. To achieve this, he attempts to manipulate the relationship between the development of Taiwan and the genesis of Ukrainian subjectivity. Specifically, he argues that any signs of Taiwanese identity, such as language, are merely a distorted reflection of mainland Chinese language. Similarly, he imposes his view on the artificiality of Ukrainian language and culture. The former Russian president seeks to manipulate the narrative by claiming that Ukraine’s language policy is not the result of the political subjectivity of Ukrainian voters, but rather an incidental maneuver by individual politicians. Medvedev further asserts that Ukrainians are simply “Ukrainized Russians.”

This very strategy — denying the subjectivity of those over whom you seek complete control — has been evident in Russian imperial, cultural, and political rhetoric for centuries. It can be traced in the rhetoric at the Lisbon Conference on Literature, in Medvedev’s article, in the treatment of historical and cultural heritage, and in the deliberate destruction of ancient Chersonese monuments in Crimea.

Chersonesus

All of these actions are part of a single imperial policy of assimilative genocide against other peoples, being carried out in a totalitarian manner by the Kremlin. The ultimate goal of such activities was best articulated by the Russian ultra-conservative political scientist Sergei Kurginyan.

In his 2008 book “Swings. The Conflict of Elites or Breakup of Russia?”, Sergei Kurginyan writes: “A conceptual war is ongoing. Or, more accurately (since the apparatus is not always strictly rational and conceptual), a war for the right to give NAMES to phenomena.” This idea is later referenced by Anton Vaino, the head of the Russian Presidential Administration and a notorious author on the “nooscope,” who, in collaboration with his colleagues, incorporates Kurginyan’s quote into their 2012 study titled “The Image of Victory.”

The empire can view any form of subjectivity solely as an enemy, because any subjectivity threatens the imperialists’ status. This is why the formulation voiced not only by Kurginyan and Vaino, but also by other Kremlin ideologists, helps explain why Russian occupiers, on Ukrainian soil, first and foremost alter the signs bearing the names of settlements and other toponyms. The Russian Defense Ministry even produced several propaganda videos on this topic. Similarly, pro-Russian politician Yuriy Boiko manipulatively raised the issue of changes in street and city names in a sensational TikTok video. In its effort to strip Ukraine of its subjectivity, the Kremlin empire weaponizes and exploits the cultural sphere.

The conventional figures of Pushkin, Turgenev, and Nabokov are, in reality, used to pave the way for Russian tanks, as can be seen from the analysis of the transcript of the aforementioned Lisbon Conference on Literature in 1988.

Paradoxically, the free world calmly accepts the cancellation of Winston Churchill — who led his nation to victory over Nazi Germany — on university campuses in the United Kingdom. At the same time, the desire to relocate monuments of representatives of the aggressor state from Ukrainian streets and squares to designated areas is regarded as extreme radicalism.

Thus, world communities protect those who can present and aggressively assert their culture, which will be recognized within the systems of “friends and foes.” In such a cynical framework, Ukrainian children who died from Russian bombs and missiles in Mariupol are expected to lose the battle for the information space to Russian opposition anti-corruption activists. Only those who can defend their identity in the harsh conditions of the attention economy will have the right to survive.

This is why the ability to name phenomena and objects, to use one’s language to generate meanings, and to harness the progress of culture to declare one’s existence is not only a sign of subjectivity but also a guarantee of the survival of both the people and the state.

At the same time, the Kremlin and its inhabitants’ seemingly programmed, genetic hatred of the Ukrainian language, the concept of Central Europe, and any manifestation of otherness is purely a defense mechanism of an empire incapable of thriving in a multicultural world. This is despite theatrical political statements about multipolarity, which, in reality, serve only as a cover for the Russian Federation’s ambition to join the ranks of superpowers like the United States and China.

The existence of a Ukrainian identity challenges the very notion of the empire, revealing it as a simulacrum. Sooner or later, if the Kremlin is forced to acknowledge Ukraine’s existence, it may find itself confronting the same issue with regions such as Tatarstan, Chechnya, or Siberia — entities that, according to Russia’s constitution, have the right to be equal parts of the federation and not to sacrifice their identity for the sake of the empire.

This is precisely the simple idea that should be embraced and understood in Western European capitals: that 40 years of constant, value-based cultural reflection on Milan Kundera’s extraordinary work “The Tragedy of Central Europe” have not led to a recognition of the existential threat posed by Russian tanks and missiles. The primary objective of these weapons is not to conquer land or resources, but to erase identity — because identity can threaten the artificial imperial existence and the crumbling imperial simulacrum of the Kremlin, which is propped up by nuclear weapons and “Oreshniks,” hiding behind the works of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy.

The revival of Notre-Dame de Paris could have been a harbinger of the realization of this idea, marking the formation and implementation of an effective strategy for supporting and developing Ukrainian identity as part of Central Europe and the broader European family.

Mykola Tochytskyi, Minister of Culture and Strategic Communications of Ukraine

Photos provided by the Office of the President, Ministry of Culture and Strategic Communications, European Parliament, and Council of Europe

Source: Mykola Tochytskyi: Culture and communication are the key to Ukrainian subjectivity