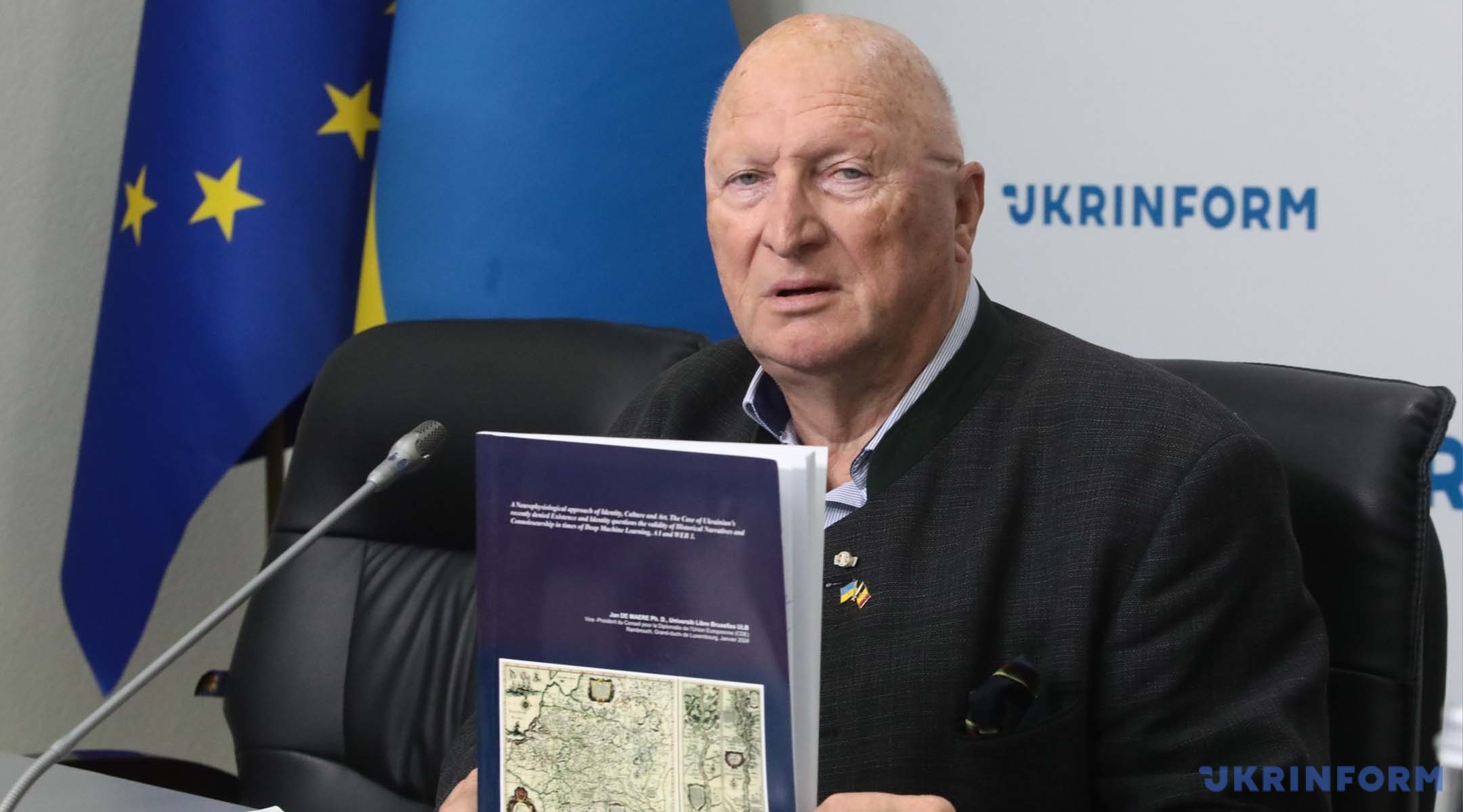

A presentation of the scientific study “Identity and the Brain” by Jan De Maere, a prominent Belgian neurophysiologist, art historian, PhD, and renowned European intellectual, recently took place at Ukrinform.

Jan De Maere is a renowned European intellectual and scholar. In 2007, he earned a Master of Science and Arts with distinction from Ghent University, and in 2011, he received a PhD in Neuroscience and Art Expertise. Among Professor De Maere’s many honors are the Legion of Honor and the Order of Arts and Letters of the French Republic. And this is far from a complete list of his awards and distinctions — listing them all would take more than one page.

Jan De Maere is also a graduate of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium, one of the most prestigious institutions in the country. Since November 2024, he has served as an advisor to the Minister of Culture and Strategic Communications of Ukraine.

The study explains how the brain forms self-awareness, how cultural and national belonging arises, and how memory, emotion, and experience influence identity. De Maere also presents arguments on how fakes, propaganda, and violence disrupt this connection.

After the presentation, we spoke with the professor and discovered that his decision to present the research in Ukraine was no coincidence. Read more in the interview about his passion for art, history, culture, neuroscience — and ultimately, Ukraine.

EVERYTHING I SAW IN SOVIET CULTURE WAS TIED TO A SINGLE CULTURAL SYSTEM

– You first visited Ukraine in the 1970s, when few in the West distinguished Ukrainian identity from the Soviet background.

– That was in 1975. I had just completed law school and ended my sports career. I received a proposal from the new magazine Knack. I also collaborated with many publications—writing for Le Monde Diplomatique, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, De Standaard—mainly on art and exhibitions. At that time, under Brezhnev, Russia was gradually opening up, and I managed to get a scholarship and work at the Hermitage. I also traveled through the Soviet Union to see it firsthand and write a few articles.

– Did people in the West already sense a distinction between Ukraine and Russia in the 1970s?

– It was all the USSR. We knew there were very different republics. I knew Ukraine was Ukraine, not quite Russia. But I didn’t see a major difference at the time. Everything I saw in culture—ballet, opera, theatre—was tied to a single cultural system. The only thing I noticed was that even back then, the level of culture here, the level of the opera, was higher than in Minsk, for example.

I also noticed a difference in how people treated me. As a Westerner, I felt more welcome in Ukraine. In Moscow, everything was strictly controlled. I couldn’t walk freely—two KGB agents followed me constantly. I became an expert at “losing” them. It turned into a game and was even fun.

What really interested me was art and creativity, but I couldn’t establish contact with Soviet artists as I could in Poland or Czechoslovakia. There, I could collaborate, buy their work, fund creativity—which later became part of my path as an art dealer. In the USSR, this was absolutely impossible.

– How did art lead you to study identity?

– That’s a long story. In 1996, Professor Robert Senelle, my academic mentor, told me, “You should write something about Flemish identity for the journal De Standaard, because the Flemish have the same problem with Belgium that Ukrainians have with Russia.” He was very pro-Flemish and influential both politically and academically. He was so invested in the project that he called me every morning at 09:30 with ideas. So I wrote a major article on Flemish identity for that newspaper.

– Was this article linked to neurobiology?

– No, it was more in the realm of psychology, philosophy, and history.

COGNITIVE BRAIN ACTIVITY WHEN THINKING AND JUDGING ART IS VISIBLE IN FUNCTIONAL MRI

– Why did you decide to turn to neurobiology?

– In 2000, Eric Kandel, for whom I did some expertise in drawings, won the Nobel Prize in Medicine. He said to me: “I want to understand how the brain works, as a neurobiologist. I’ll study your Connoisseur brain.” I couldn’t move to Columbia (for this purpose), but we began working on a concept explaining how we perceive what we see in art through f-MRI neurophysiology. That’s how I began diving into neurobiology.

Semir Zeki, from University College London, brought me to the Wellcome Institute where we examined brains of connoisseurs. Jean-Pierre Changeux, Institut Pasteur and Collège de France, Lionel Naccache, CNRS La Pitié Salpétrière, François Michel, Clinique du Sommeil, Université Lyon and Mark De Mey Ugent, were members of the jury of my PhD concerning neuroscience. Joost Van der Auwera, curator Brussels Museum of Fine Arts, Koenraad Jonkheere Ugent, and Maximiliaan Martens Ugent, the director of my research, were the jury. During 5 years, I worked under their supervision. Now I work with my colleague Guy Cheron, who advised me on the neuroscientific part of this study, at the Lab of Neuroscience of Mobility at the Brussels-based ULB University.

– Why did you undertake an interdisciplinary study combining identity and neurobiology?

– Our personality, our identity, is a state of consciousness. Today, we can identify what constitutes the physiology of consciousness—what brain regions are involved.

– It’s easy to observe a response to a masterpiece, but how can you study identity?

– The brain communicates chemically via neurotransmitters, and via electricity. All brain cells specialize in certain functions but originate from the same stem cell types. When they “travel” to the right place, they get signals about what to do when arrived. The cognitive brain activity when thinking and judging art is visible in functional MRI. When you look at something, your judgment is an emotional feeling that pups up as a blink—You can feel it as an embodied brain experience. Because emotion is an automatic intuitive physiological reaction. 99% of what we intend do is directed by automatisms born out of our experiences. Less than 1% consists of conscious new decisions of our free will. Both are formed in the frontal brain lobes—this is where our free will lies: the ability to stop an action prompted by automatism.

That’s why we can judge psychopaths and narcissists—if they can stop themselves at certain moments and not at others. A psychopath won’t attack someone in a lit room—he’ll follow them into a dark alley. That’s a plan, and therefore: guilt. A spontaneous, contextless attack would be illness. That person should be isolated, not judged.

PUTIN DOES NOT BELIEVE HIS OWN PROPAGANDA — HE KNOWS IT’S MANIPULATION

– As a journalist, I have to ask you about fakes and propaganda. They don’t appeal to logic; the goal is emotional manipulation…

– True. But it depends on your critical experience and the quality of your expectations. Identity is also experience.

– Can fakes and propaganda destroy our identity?

– No. Only you self can destroy your identity—if you allow yourself to be intimidated by the judgments of others.

– Russia wages war not only on the battlefield, but also in the information space. What advice would you give to Ukraine’s Ministry of Culture or communication experts?

– Develop critical thinking, engage in open dialogue about your own history, and don’t oppose one fake narrative with another official one. The heart of the Ukrainian people will shape its own history—something concrete and emotionally resonant. There are scholars like me—but there are also Ukrainians, such as Serhii Phlokhii at Harvard University, with a critical eye on your history, your figures, your art, music, and literature. This leads to open discussion, critical thinking, and self-awareness that makes fake news and propaganda look absurd. Like with wine—once you’ve tasted the real thing, you can’t go back to bad wine.

– But what you’re describing is a long path. And we need answers yesterday…

– I have far more expertise on Northern Renaissance and Baroque paintings than in Ukrainian culture and history. I studied Northern European history to understand how, despite shifting borders and empires, a sense of unity—of emotions, aspirations, and a shared vision—still arose. And it’s clear now: the people fighting for Ukraine want a future for Ukraine which includes their values. They want that future together. They want unity and a sense of belonging.

We began this conversation with how Ukraine’s identity was perceived in the 70s, and how it’s seen now in the West. Let’s say this: until 2014, few people saw a clear distinction. It was evolving, like in many regional centers. But since 2014, everyone in Ukraine started asking: what are the pillars of my culture? In art, painting, music, literature, poetry, politics. Ukrainians want democracy, law, and freedom of speech. They don’t want a nomenklatura or dictatorship. They don’t want a “superman” who isn’t even an ‘alpha male’, but a petty dictator.

People understand this. They ask: what do I want for my future, for my children, for myself? What are my anchors? The village church I was born near. The small grocery where I buy vegetables. A little restaurant I once ate in. A church, a theater, opera, books, newspapers, neighbors—everything that gives me comfort.

Identity is a feeling of home. It’s the feeling of belonging and hope—being accepted for who you are. No one’s self-narrative is 100% accurate. We always embellish a little—because we want to be better than we are.

There are people in power who know they’re scoundrels. Someone like Putin does not believe his propaganda, he knows it’s manipulation.

– I disagree. I think he sees himself as perfect.

– No, no. He thinks has a mission to restore the Russian Empire. There’s plenty of research on hyper-narcissistic individuals showing this behavior stems from deep insecurity. Dictators aren’t brave and virtuous. They aren’t the ones who rise and fight. Every time Putin faced hard opposition, he backed down. He is smart.

– He just found another way to overcome resistance…

– Over the past 20 years—since 2005—he’s been very successful. Hybrid war—on all levels, including internationally against Western values and democracy. Thanks to Schröder, Merkel, and Scholz, Germany became fully dependent on cheap Russian energy. This was not wise strategically.

– Maybe now that will change?

– Yes, but it comes at a high economic cost. Merkel was warned. Schröder too—that it was dangerous to entrust your country’s economic future to someone who is not your friend. So now the question is: were they friends of Germany or of Russia?

The entire Soviet economic system was based on supplying cheap energy to make the West dependent. In the West, people didn’t recognize cultural differences in he 30 different regional-ethnic cultures in the former USSR, because countries like Ukraine, Azerbaijan, etc., didn’t present efficiently enough their cultures as distinct.

I first heard, maybe only ten years ago, that Malevich and Repin were Ukrainian—and that became part of my research. War has some positive effects for a country’s collective identity. At least now we understand there are cultural differences.

It’s now clear that Ukraine has its own culture. At times close to Austro-Hungarian (18th c.), to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (late 16th–17th c.), or to Soviet in the 20th—but always with its own idiosyncrasies, its own features that let you recognize Ukrainian art as uniquely Ukrainian, its music as uniquely Ukrainian. The people who created it genuinely wanted to be different.

Interviewed by Tetiana Pasova

Photo credit: Volodymyr Tarasov

Source: Jan De Maere, Belgian neurophysiologist and art historian