After graduating from military academy, he planned to serve his first contract and then go to an area of conflict in a foreign country. The dream came true, except that he had to fight for his home country. In 2014, Yevhen Zhar went to the east of Ukraine, and now, in 2025, he and his comrades are holding the defense on Ukraine’s northern border.

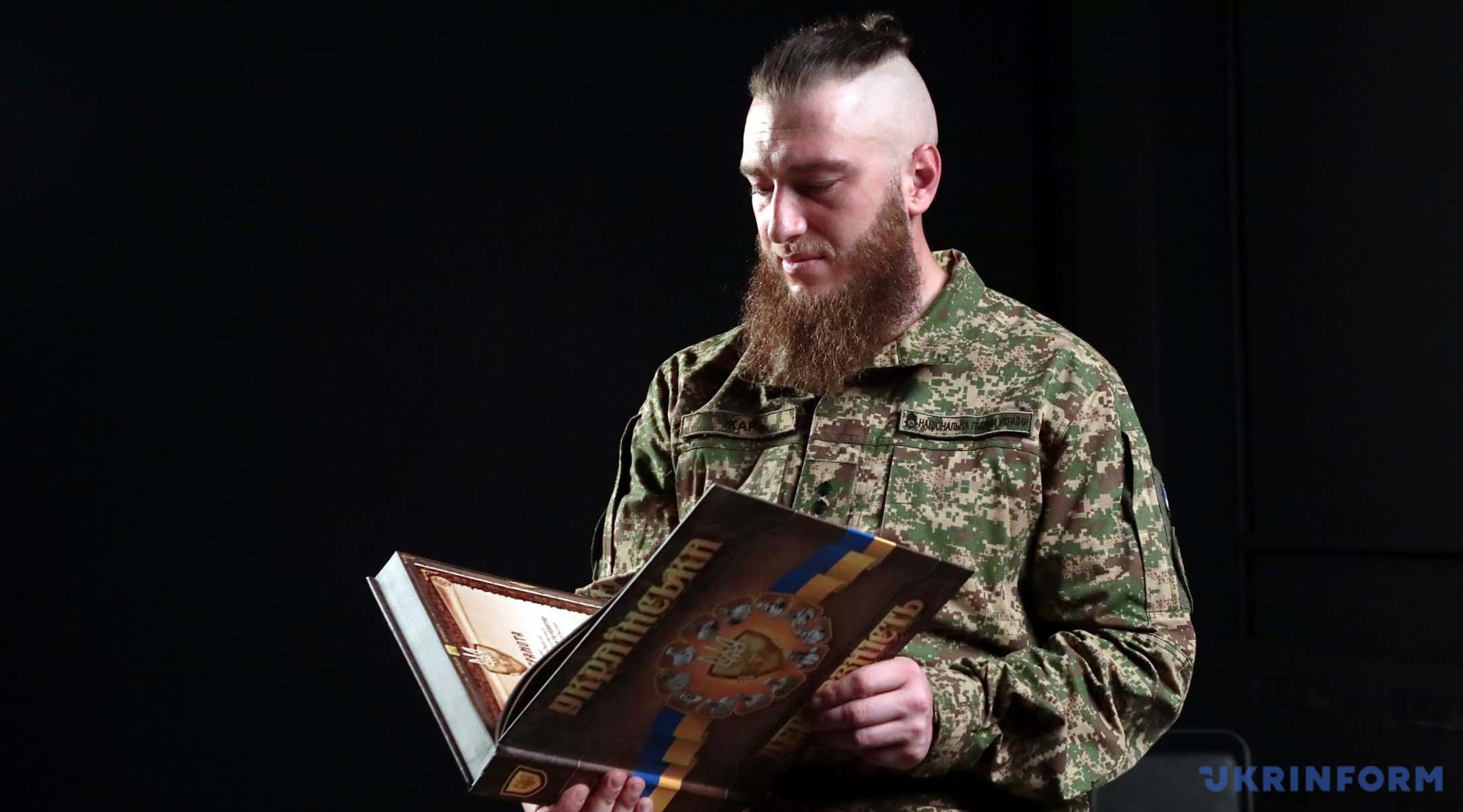

For this Victory Commanders series interview Ukrinform invited Yevhen Zhar, National Guard of Ukraine Colonel and military unit leader, to talk about his combat career, the specifics of service in the Chornobyl NPP exclusion zone, dealing with the effects of Russian attacks, unique operations of special forces units, rehabilitation after injuries, and veteran sports. We additionally discussed the possibility of a large-scale Russian assault from Belarus.

[embedded content]

– Mr. Colonel, you chose the path in the military back in 2008, despite your father trying to dissuade you from this choice. What motivated you to choose this career?

– I will correct you a little bit. I decided to be in the military after my father returned from a business trip in 2006 and brought along a brochure titled “Academy of Internal Troops of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine”. I saw from the pictures how cool it was, read it and then I was excited to join the military. My father tried to dissuade me for two years until 2008, saying, if you want to choose military career, understand that with each year of service, with each career step, there will be increasingly less personal life. But in 2008, he accepted my decision, as he said, “I accept it as a given, but know that I do not really agree with it.

– The war for you began in 2014. Do you remember the day when you received the signal for soldiers to assemble? How was it?

– It was a Saturday, a regular day off. We received the call for “Assembly” and 40 minutes later we, already armed and equipped, arrived at the airfield. We loaded into a helicopter and flew out. First to Kramatorsk, and then further to Izyum. It all started there on April 12.

– What tasks were you assigned to perform then?

– This was a set of various tasks ranging from escorting top state officials and mop-up operations to ambushes and escorting vehicle convoys, both humanitarian and military.

– Which of the missions were the most challenging for you at that time?

– At that time, we for some reason didn’t really think about whether the task was challenging or not. We all were learning to conduct combat operations as if we were not born to fight right away. One can learn this and gain experience for use it the future. I thus cannot single out any task, the one that was the most challenging for me.

– When did you find yourself in a real combat environment, see your first real-world combat experience? Not the one described in textbooks, or imagined before. What did you feel?

– At the moment, the feeling was probably like a euphoria, sort of, the one I had when celebrating a New Year at home, and my father asked me about my plans for the future after graduating from the academy. I said that I want to serve my first contract, as I should have, and then go to fight in an abroad area of conflict. It just so happened that I had to fight at home, unfortunately. Therefore, for me personally, it was a light euphoria, because after all, at that time I was a military man serving in a special forces unit, have gained some experience, knowledge, skills and a feeling of what war is like, when you are being shot at and everyone in that damn forest aims to kill you.

– Did you ever regret your choice, remembering your father’s words?

– No, I never regretted it. He just was asking me from time to time about whether I liked it, or regretted that I made the wrong step in my life? I always replied no, I don’t regret it. And then, when he realized that I was succeeding after all, and began to support me, to give me some advice from himself, he was proud of me. And he supported me very much. Even if his advice was inappropriate at the moment, I still took it into account. You know, a commander always makes a decision based not on one option, but from at least two. And so did I.

– Did you heed?

– My father’s advice, plus my personal opinion – and I already have two options to choose from and will act one way or another.

– As far as I know, you met the full-scale invasion while serving in the Luhansk sector. Did you have a feeling the day before that something bad was going to happen?

– Yes, I did. I encountered the full-scale invasion while deployed near the town of Shchastya, Luhansk Oblast. My unit and I were deployed in the most forward-deployed area of operations, at the tactical edge, as is said. And three days before the full-scale invasion, we already understood that something was about to begin. And on the night of February 24, I ordered my guys to get ready for an artillery barrage possible in the morning. And I was right. Thank God, everyone was alive. On the first day, I had only one wounded casualty, a mine shrapnel wound in the arm. But everyone exited the position safely and continued to execute the tasks that followed.

– Did you have a premonition of what it was?

– We have the means to intercept their radio talks, plus intelligence, foreign intelligence service. All allied units share intelligence they have, so even back then we understood that something was going to happen. And, as they say, the human factor is the commander’s spidey sense, which, thank God, has never failed. That day, happily, it did not fail either.

– Did you hear the wiretap intercepted Russian conversations?

– Yes. And we even read the messages they shared through messaging apps. And one and the same message was repeated for three consecutive days.

– What were your further actions after February 24, 2022? And what tasks were you assigned to do?

– Since I was serving in the Omega special forces unit of the National Guard of Ukraine at the time the full-fledge invasion began, the tasks were primarily specific counter-sabotage operations, such as preventing military vehicle convoys being captured, or conducting counter-sabotage measures at brigade-to-brigade junctions, or in the depth of friendly territory. I, unfortunately, served in the special forces unit for only 2 weeks after the start of the all-out invasion before being transferred to serve with a line military unit that provides safety guarding for important facilities in the city of Pavlohrad.

– Which operations stand out most in your memory (if, of course, they can be discussed in this conversation)?

– I haven’t forgotten a single operation. They all are sealed in my brain — from the routine escort of particular individuals (such as governors, top government officials, National Guard leaders or Cabinet ministers) to particular locations, to entries into tactical edge or gray zone areas, where the range of the tasks for special forces has no limits.

– In 2023, you already led a force that provided security and guarding for the Chornobyl NPP. We all saw and heard about what the Russians were doing at Chornobyl and the surroundings. And then everyone was extremely amazed seeing the mad things they did digging holes in the Red Forest, completely disregarding safety concerns. When talking about our warriors currently performing certain tasks in the Chornobyl zone, how do we take care of their safety?

– We constantly monitor the radiation exposure levels in the first place, for which we have all the requisite equipment. And no one goes to perform tasks, to do service in a location where a chemist armed with a dosimeter has not first passed. Even if people are standing there and everything is OK, it’s mandatory that the chemist personally goes through and inspects every position, every path at least once in a week. And if any changes are detected, we immediately change our place of deployment.

– Would you tell us about your unit? What makes it unique and what makes you proud most?

– The unit is unique in that we are working at a very unique facility, which is the only non-operating nuclear power plant in Ukraine out of five, of which one, in the city of Enerhodar, is currently under occupation, and the Chorobyl NPP is non-operational. The NPP site and the surroundings, as everyone used to say before, is an attraction for tourists, stalkers, because it was a tragedy of the really terrific extent at the time, which left behind a terrific aftermath. As regards the uniqueness of our unit, we have learned to handle it, to take care of safety, to ensure that this never happens again, to prevent it. I am most proud of the fact that people join our ranks, people learn, people take care of their own safety in the first place, keep civilians calm, and the fact that they do not give in to an a serios challenge such as radiation. Because this is such a thing that you can neither see nor touch. This is a very insidious story, to be honest.

– To my knowledge, on the day when, as we remember, the Russians targeted the Chornobyl NPP confinement arch, were you there?

– Thank God, we, together with all the services that were dealing with the effects of attack on the Confinement, everything worked out well and the radiation exposure level did not change, did not rise, and everything was OK. But there are some troubles regarding the operability of the confinement arch cooling system. It was damaged.

– Why do you think the Russians do this while realizing the cost of the disaster that could have happened?

– The cost of the mistake could have been high, very high. And why did they do it? I never look for logic. To be more precise, I am looking for it, but can’t find logic in what they are doing. Take Enerhodar, for example, where they fought with our servicemen who were guarding and defending the station during its capture. And they, without thinking a lot, fired shots from tanks at the station buildings. What do they leave behind? Nothing but burnt-out cities, destroyed, reduced to ruins, so we look for logic, but, unfortunately, don’t find it.

– Thank you for this answer. What does being a commander mean to you? And, in your opinion, what should a perfect commander be like?

– Let’s start with the fact that there is no such thing as a perfect commander. There will always be losses in war, and where there are losses, it means that the commander did something wrong. The commander must do everything he can and even more to preserve as many lives of his personnel as possible and then execute the task at hand. For me personally, being a unit commander means a very big responsibility, because you have a lot of people behind you who trust you, believe in you and are ready to follow you anywhere and do everything they can to carry out your orders. But it also leaves a very big imprint when you organize a unit, train it, invest yourself, and if, unfortunately, there are losses, because there is no war without losses, then it really sticks somewhere inside you.

– You said that preserving the lives of the personnel is what means the most to you. And I heard you saying this in your previous interviews. How exactly is a commander able to ensure that as many lives of his subordinates as possible are preserved?

– To teach them to fight, employing the experience of my own and the experience of the instructors who teach my people. Plus the integration of the latest technologies, most particularly unmanned systems — FPV drones, ground robotic systems, surface drones. This all has to be integrated into the battlefield, and it is better to lose a drone, no matter how high valued it is, but preserve a human life. People are the most valued resource in war.

– Which of your decisions was the most difficult to make?

– I will probably be unable to single out any such decision. But each decision involving an order to enter a certain operational zone to perform tasks, understanding that losses may be suffered there, is very difficult to make. That is why it is invariable that we, when serving as part of a special operations unit, go on a task with a full team. And, praise God, we were able to return everyone home alive.

– Speaking in this studio with different commanders, we see that everyone employs management styles of their own. How would you describe yours? What do you focus on the most, what is most important to you?

– The most important thing for me is people’s trust. And people’s trust is not gained in one day. I am a commander, my management style implies absolute trust in junior commanders, in subordinates, in battalion and platoon leaders. And I allow them complete freedom of action in executing their assigned missions, but within the framework of legal norms. And if they succeed, they are full-fledged commanders who can work autonomously, independently of each other. Because at the time when I led a platoon, I was instructed where to go, what to do, why to do it and how much time to do it. And this is exactly the experience part of which needs to be put back in use, and I have such an opportunity to start changing, not even start, but contnue to change this army, our army, so that people are willing to serve. On top of that, we in our unit and the Brigade as a whole are prioritizing a person’s conscious choice of the position one wants to hold. Some may misunderstand these words. I mean to say that if a person wants to become a drone operator, then let him be a drone operator. If a person wants to become a machine gunner, then we will do everything to make sure he becomes a machine gunner. So that it doesn’t happen that you just appointed a man to the position of drone operator, but that isn’t good for his soul; he doesn’t understand anything at all about those quadcopters, FPV drones, what copters are, he doesn’t see the difference. Therefore, this is one of the aspects that lies in the basis of my personal management style.

– Doesn’t this cause a certain imbalance, where everyone wants to be a drone operator, for example, but few want to be infantrymen?

– No, there is no imbalance, since everyone who wants to tries himself. We have all the means and opportunities for that. They try themselves and say: yes, I tried it, that doesn’t suit me. I’ll better go back to do what I did, to be a machine gunner, for example. This happens. It happens that a person has switched from one specialty to another, then goes to perform combat missions, comes back and says: this is not easy, I liked what I did before. Can I go back? Go if you think you will be more useful there.

– What is the situation with the number of personnel? Do you have enough people, or do you need to recruit? Do you recruit on a regular basis? Do new fighters join in?

– People are in short supply everywhere. I don’t mean to say this shortage is critical, but people are always needed, because we are continuously growing, continuously expanding. We keep up with the times, add new subunits, look at how National Guard units are fighting, and not only units of the National Guard. And we try to keep up with them. Besides, the people applying for a transfer to the National Guard or other uniform service, but to combat units only, can be transferred with ease. I will only support such choice and give some advice from myself about which unit is better to choose.

– How can people join you? Is there any recruiting company helping you?

– Through Facebook, Instagram, where there is all the information about how people can join us.

– What are the most serious challenges currently facing you, your unit?

– Our unit is facing only one challenge, and this is a very short distance to the border with Belarus. And we are preparing to see the enemy coming in, as in 2022, from Belarus or through its territory again.

– Do you see any signs of Russia preparing for a new offensive from Belarus?

– Regardless of what actions are currently taking place on the territory of the Republic of Belarus, we are preparing for any scenario possible.

– I know that you play sports and participate in marathons as a veteran. Could you tell us about this hobby of yours, how does it help?

– Sport is helpful in that it puts your mind in order in the first place, even where you are away on combat missions, as it used to be during the ATO/JFO [Anti-Terrorist Operation/Joint Forces Operation) campaigns in eastern Ukraine. I could find time and devote myself to physical training to the full extent. As regards the veterans’ marathons, that was, you know, probably a childhood dream. After all, this distance – 42 km 195 m – not everyone is able to run it. I set myself a challenge, but I couldn’t get there, I just ran, practiced. In 2017, I decided to register for a marathon, I was training myself for six months, including three months while being away on a rotation during the Joint Forces Operation. I ran my first marathon in the city of Kharkiv in 2018. It turned out to be very difficult. During that time, you curse yourself, you’re proud of yourself when reaching the finish line. But before that – you curse. And then, when you already feel pain in your whole body, you start cursing yourself again. But not even two weeks later, I was already signing up for the next half marathon. Half marathon is probably my most favorite distance. It runs easier. And officially, I ran the full marathon only twice – in 2018 in Kharkiv and in 2023 in London. Already in the status of a veteran, I received an invitation and ran. But in London, I ran without preparatory training. Unfortunately, I didn’t have time, and my health didn’t allow me to get prepared as appropriate for the marathon. But I still was able to run it through to the end.

– Do you have any other plans for the future, maybe any dreams?

– Yes, of course. If possible, I will participate in veteran competitions, which, luckily, are very popular today. These competitions are increasing in numbers, with new ones added every year. There are one or two sports regularly added to veterans’ competitions. I also don’t give up my dream of trying out triathlon once in my life. It’s a very powerful story, but you have to prepare very hard for it. For me, the most difficult part of it is swimming, at which I am still poor. I can swim, but it’s so far too hard for me to swim three kilometers and 800 meters in open water.

– Did you get your first injury during the ATO?

– Yes.

– How did it happen?

– It was a routine mission, nothing too complicated. Mop-up raids in some settlements and measures to prevent the Donetsk airport from being encircled and captured by separatist rebels were to be done in areas surrounding the airport. There was a stretcher set up on a path in the field, and a fragment of it hit my face near left eye. But they quickly poured hydrogen peroxide on it, put on a plaster – and I continued to perform the task alongside everyone else. And only after the task was completed, when we returned to the base, was I taken to the hospital, an X-ray was done. It found no fragment. I was treated a little to relieve the inflammation of the soft tissues, and then I continued to perform the tasks. Then followed one shrapnel wound, and in 2023 I received a closed craniocerebral trauma, an acubarotrauma. In simple words, it is easier for civilians to explain – a severe concussion. My hearing and vision were a little bit off, and blood pressure jumped high. I was treated and immediately after undergoing treatment, I returned and accepted this position, the one which I currently hold. But no injury, no concussion goes without a trace. Therefore, I need to undergo treatment once in every six months just like a car needs to undergo routine technical inspection.

– How did you endure this all, didn’t you lose heart? What was the rehabilitation like, how did you go through it?

– In 2014, rehabilitation was very simple – I was sent on leave by order. I didn’t go on rotation with everyone else, I went on leave. I was given infusion therapy and a medication course. And in 2023, I underwent the same treatment, but under the close supervision of doctors, since my vision and hearing had already suffered a little bit, and they helped stabilize the pressure. Rehabilitation? The leave and rest were probably my best rehabilitation. Why didn’t I lose heart? Because since 2014, I have a lot of friends who have lost their arms, legs, and vision, some of them are in wheelchairs. It’s much harder for them. I look at them – they run, play sports, swim, shoot, drive cars, those guys who are in wheelchairs. I myself have everything in place. My arms, legs, everything else is in place, why should I be distressed while they are not. No, I should not. And it is thanks to such a wide circle of acquaintances, unfortunately, due to the war, that I don’t just give myself a break.

– What would you advise to those who may have just been injured and are at the beginning of this path, at the beginning of rehabilitation?

– Join the nearest veterans’ organization, those who are rehabilitating through sports. It’s vital not to sit at home, not to sit alone, not to turn inward. Look for connections somewhere with likewise people, with similar injuries or traumas. Look for like-minded people and, through sports, drive all this stupidity out of your head and socialize. After serious injuries, socialization is what means the most. Our society is already learning to perceive people with prostheses and wheelchairs normally, but it is still learning, unfortunately.

– What else needs to be done to improve this aspect, so that society perceives it better?

– We should probably start with the elementary, with school-age children, all those who study at school, take them to rehabilitation centers to meet the guys. They can just come and talk, so that children, from grade 5 to the graduating grade 11, for example, see the young veterans who, despite hurt and pain or being unwilling, get up on prostheses, learn to walk on them, learn to ride in wheelchairs, learn, having arm amputations, to take care of themselves, to eat by themselves, do the most essential things. So that children see this and understand that these people are military, they’ve sacrificed their greatest asset – their health so that those same children could study at school. And when children understands this, they will carry it on and from their childhood will understand the cost of freedom.

– How do you generally assess the veterans’ rehabilitation system in Ukraine?

– It’s quite good, but too sluggish, to be honest. In large cities, only one or two gyms out of 10-12 are actually accessible for people with certain health limitations, particularly people with high leg amputations or moving around in wheelchairs. Unfortunately, you can scale this to any numbers, but the statistics are such that no more than 20 percent of gyms in large cities are accessible. I would also recommend scaling up a story such as Government-sponsored sports for veterans. The money contributed for this project is scarce, unfortunately. I doubt that in a city such as Kyiv, for example, you can buy a monthly gym membership for UAH 1,500 (less than USD 40). And in smaller cities, settlements, towns or villages, there are guys who suffered severe injuries, but they have nowhere to go to play sports, to keep in shape. I therefore reiterate the need to expand the network of sporting establishments and veteran’s communities so that they reach even the smallest villages where there are such people.

– In this studio, we often discuss issues of importance for our country. Victory. What will Ukraine’s victory mean to you personally?

– For me personally, it will mean the preservation of sovereignty and our independence. This is what victory will mean to me. Looking at the current situation, it will be hard to achieve, indeed, but we have been repelling the world’s second army for longer than three years now. If we preserve our independence, learn lots of lessons, integrate them into our life, increase our military strength and readiness, whatever you want to call it, and be ready to meet the emerging challenges and not repeat the mistakes we’ve made in the past, that’s where victory will lie for me.

– Thank you for this answer. Our interview is slowly coming to an end, but we, as tradition, request our guests to answer a series of rapid-fire questions. Please, answer the first thing that comes up for you. Ready?

– Yes.

– War is…?

– Pain.

– What can you never forgive?

– Betrayal.

– What thought do you wake up with?

– Thank You, God.

– Can one person change the course of history?

– Yes.

– What is your biggest fear in life?

– Losing loved ones.

– What is the greatest reward for you?

– Preserving the lives of my soldiers.

– What does independence mean to you?

– Freedom.

– What will you do first after victory?

– I will turn off the phone.

– Well, thank you! Ukraine will hopefully win a fair victory as soon as possible.

Diana Slavinska led this conversation

Photo: Volodymyr Tarasov

Watch this interview in full on the Ukrinform TV YouTube channel

Source: Yevhen Zhar, National Guard Colonel, Military Unit Leader