When Ukrainian children in occupied areas return to school on 1 September, history lessons will be taught very differently. The BBC has discovered that Ukrainian teachers are being pressured to use the Russian curriculum, which means studying the world according to the Kremlin. Most names in this report have been changed.

In the occupied areas of Ukraine’s south, administrative and educational buildings – including schools – have been dressed with Russian flags. In Russian-controlled Melitopol, Iryna’s 13-year-old child is getting ready to begin the 8th grade. Iryna is worried.

“What really bothers me [about the Russian curriculum] is what they’ll be taught in history. It will be taught from the ‘other side’,” she says. She’s also angered by lessons being held in Russian rather than Ukrainian: “It’s the imposition of their traditions and culture – I do not want the children to be hostages to the situation,” she said.

- ‘My city’s being shelled, but mum won’t believe me ‘

- How Russia replaces Ukrainian media with its own

Users of pro-Russian social media channels have boasted publicly about the attempted erasure of Ukrainian history in occupied areas.

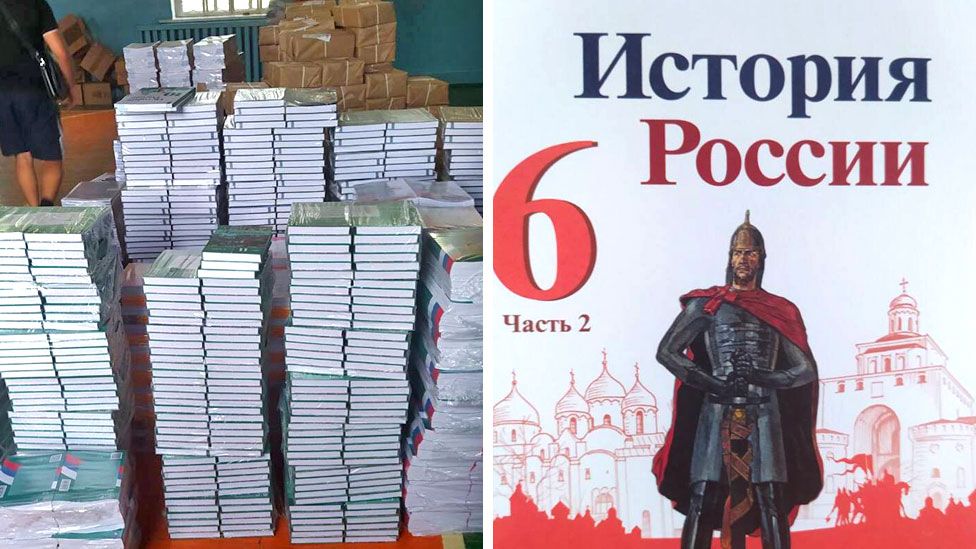

There are regular images of Russian forces removing Ukrainian history books from libraries, while Russia’s so-called Ministry of Enlightenment has started to provide several occupied areas of Ukraine with Russian textbooks.

The BBC has analysed the content of the main school textbooks approved for use by the Ministry of Enlightenment and the differences with their pre-war 2016 and 2022 editions.

Most references to Ukraine and Kyiv were removed. Even “Kyivan Rus” – the name of a medieval Eastern European state with its capital in Kyiv – was replaced with the name “Rus” or just “Old Rus”.

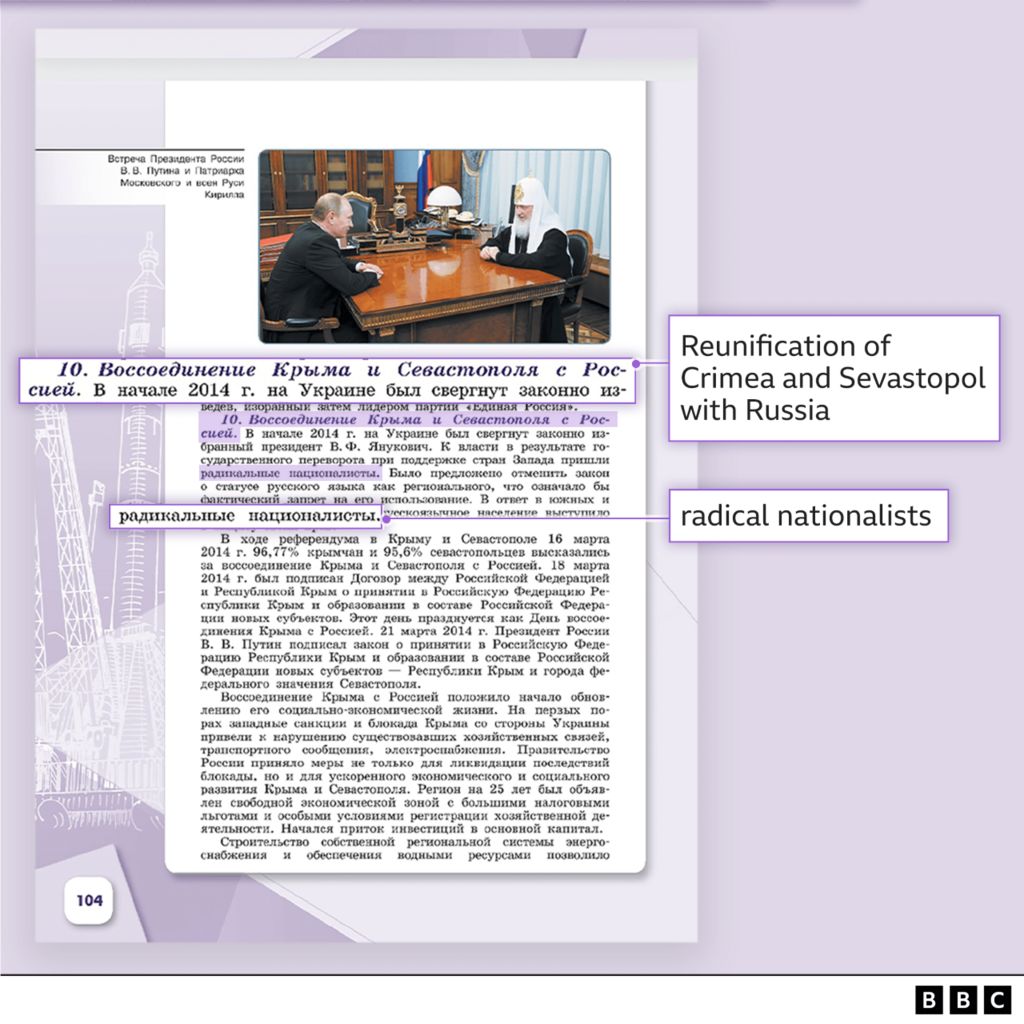

The books include false statements that during the Russian annexing of Crimea in 2014, people came out to “protect their rights” after “radical nationalists… came to power [in Kyiv] with the support of the West”.

Meanwhile, in the current version of the textbooks, the number of references to Putin and his achievements has grown.

The BBC contacted Russia’s Ministry of Enlightenment but did not receive a response.

Iryna has considered leaving for Ukraine-controlled areas but doesn’t want to abandon her home. She’s adamant that she doesn’t want her child to learn under the Russian curriculum, but is concerned about keeping her child at home. In principle, children can learn the Ukrainian curriculum online, but parents are concerned about repercussions.

“What if someone informs on us to the new [Russian-installed] authorities or if they start persecuting me and my child for not receiving a Russian education?” she says.

On 19 August, a post on the social media platform Telegram from a local pro-Ukrainian outlet quoted a message allegedly sent to parents from a pro-Russian teacher at a school just outside Melitopol. It said that there will be “no remote learning on our liberated territory,” which is how the Kremlin describes occupied areas.

Parents who refuse to send their children for in-person teaching would be “stripped of parental rights” if they violated the rule multiple times.

Meanwhile, parents who agree to send their children to schools in occupied regions of Ukraine will be rewarded. On 24 August, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the one-off payment of 10,000 rubles (£140) to parents, as long as their kids attend a school by 15 September.

Teachers tracked and deported

Pro-Ukrainian teachers have also been hit hard by the war, with some forced to go into hiding, sent for ‘re-training’ and threatened with deportation.

Dmytro, a headteacher in Melitopol, had a bustling school of more than 500 pupils before the invasion. Now he’s in hiding after being sought out by Russian officials for trying to organise for students to learn the Ukrainian curriculum online.

He says he knows teachers who were either forced or decided to cooperate with Russian officials and were sent to Crimea or Russia to be re-trained in a way that’s palatable to the Kremlin ideology.

“They were told, ‘we’re Russia, we’re one people. We should be united,’ and that these narratives should be passed to children,” he says.

While Dmytro has chosen to stay in Russian-controlled areas, many teachers and parents have decided to leave.

Marina, a teacher from Nova Kakhovka in the Kherson region fled at the end of July. Her decision came weeks after armed Russian soldiers and a Russian-installed head of education announced that they were shutting her school because the headteacher would not cooperate with them.

She says she has heard of staff shortages in Nova Kakhovka, with some teachers having to teach multiple unrelated subjects. She’s worried that the Russian-installed education system will be detrimental to children’s sense of identity.

“Their main task is to brainwash and to put their own narratives into a child’s mind. They want our children to forget what country they’ve been living in, to forget who they are.”

Historical revisionism

Leonid Katsva is a Russian author who has taught history to school pupils in Moscow for 42 years.

He has seen how history has been misrepresented in Russian textbooks. In the case of the 2014 annexation of Crimea, he says there are “no mentions of activities of any Russian forces in the peninsula.”

In the next school year, Mr Katsva believes books will likely feature a tough assessment of the West’s activities. “Textbooks that are being rigidly moderated now will fully follow the line of Channel One (Russian state TV),” he says.

“This is a clear evidence that the Kremlin uses school education as a propaganda tool”, says Dmytro from Melitopol. However, he hopes that even with a limited access to an online version of the Ukrainian curriculum, children from his region will still be able to learn the true course of events and have a clearer understanding of Ukraine’s recent history.

“Our kids keep asking why their schools have been dressed with a flag of another state. What can I say… Even six-year-old children understand this is not normal.”